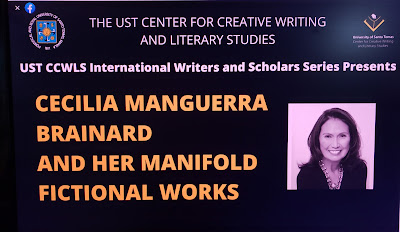

Filipino FilAm Author Cecilia Manguerra Brainard gives a talk for the University of Santo Tomas Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies. This is part of their UST International Writers and Scholars Series.

This same video can be viewed in the Facebook site of UST Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies:

Following is the transcript of Cecilia's talk:

Celebrating Writing and My Selected Short Stories

For the International Authors Series of UST Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies

by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, copyright by Cecilia Brainard

Thanks to Professors Jing Hidalgo Pantoja. Ralph Semino-Galan, Jack Wigley and all at the UST Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies for inviting me to give this talk. I am honored and grateful to you for including me in your literary family.

This talk gives me the opportunity to celebrate my book, Selected Short Stories, which was recently released by the University of Santo Tomas Publishing House and PALH. The book collects 39 of what I think are my strongest and most interesting short fiction.

The book is divided into three parts: Part 1 includes stories set in my mythical place, Ubec; Part 2 has stories from other parts of the Philippines; and Part 3, many of which are more recent stories, are set in other parts of the world, including the US, Mexico, France, India, Peru.

To give you an idea of my writing, I’d like to share a short reading from Part 2 of my Selected Short Stories, a story entitled “Romeo.” The piece recalls the puppy that I bought in Escolta, when I was in college. My niece and I saw a man holding out puppies for sale, and on a whim I bought one and named it Romeo. This story is about that beloved dog, but it’s also about my mother, and it’s also about the Marcos years in Manila. I’m reading from the last part of the story. (Read from “Romeo” from SELECTED SHORT STORIES BY CECILIA MANGUERRA BRAINARD)

That was from the story “Romeo":

Ralph and Jack sent me questions – thank you for these --and I will start by responding to Ralph’s first question:

1. Which writers, Filipino and foreign, have influenced your fictional writing the most in terms of thematic concerns and literary style?

When I was learning the craft of writing stories, I read the classics, some of which I had read in college, and which I reread with interest. I wanted to learn how the writers put their stories together, how they created interesting and fleshed-out characters. I observed how they handled dialogue, plot, setting, and other elements of fiction writing. I noted their elegant language, how they strung words and phrases together. I wondered how an artful writer and one who wrote simply could be equally effective.

Aside from looking to these writers for tips on how to write better, I was trying to find an answer to an important question: What is writer’s voice? How was it that Graham Greene’s work could not be mistaken as the work by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, for example?

There is a bit of background related to this question of Voice.

When I started writing stories, I didn’t have a strong handle on Voice. Even though I could create stories, they had a somewhat generic feel to them, so much so that once I was told by a work shopper that my work could have been written by a graduate from Sacred Heart College in New York -- a critique that stunned me since I was born and raised in the Philippines. I had to stop and think about the problem.

Once I had pinpointed that my Voice was off, I studied the fine writers to see how they conveyed their own writing voices. I also observed how these writers handled style, language, character and character development, conflict, plot, and all the nuances that go into fiction writing.

My best teachers on “Writer’s Voice” were the once whose works I read in translated English: Gustave Flaubert, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and Fyodor Dostoevksy. Think of this: their works were originally written in another language. I read the English translation of their works, and yet, I knew I was reading work by a French, or Russian, or Latin American. I was able to pick out their unique writing voices. I could tell I was reading Flaubert and not Dostoevsky, for instance.

How did they accomplish that? It had to do with their setting, with the characters that were authentic to those particular places, their conflicts, their culture, their values. I always felt some presence of the writers right there on the page, and so I could not confuse work by Marquez with work by another writer.

My teacher for dialogue was Graham Greene. If you want to learn how to write good dialogue, read Greene and note that his dialogue never shallow. Every sentence uttered reveals something about the character speaking.

Gustave Flaubert taught me how to create and develop characters. If you think about it, Madame Bovary could have been a cheap romance novel, but it’s a classic. How did Flaubert accomplish that? By creating complex and memorable characters.

There is another thing that Flaubert taught me about characters. Sometimes characters you are creating are very similar, like seeing white on white, a writer (Flaubert) had said. So the fiction writer’s job is to differentiate the colors somehow. In other words the writer has to dig deep to be able to differentiate one character different from another.

Cecilia and Lina

Still another writer who influenced me was our writer Lina Espina Moore. She reinforced my ideas about Voice. Lina’s stories had a distinct Cebuano flavor.

She was Cebuana like me and she had novels and short stories written in English and Bisaya. I remember her telling me that she used to dash off stories for publication to help pay for the school tuition fees of nephews and nieces that she helped support. She used to give me advice such as: “Write like you talk.” Well, it’s not exactly that way for me, but I understood what she meant; she meant, don’t be ma-arte. Don’t be pretentious; just write like you talk.

I also reread Jose Rizal, not just as a study for the Filipino Voice but to see how he handled the historical aspect of his novels. He wrote about characters whose lives were shaped by historical events. Rizal’s characters had internal as well as external conflicts to deal with; I could see that his characters had to react to the historical events that’s ongoing, that in fact, their lives were shaped by these historical events.

Another important influence on my writing were our Philippine epics. Here in California, the folklorist Herminia Menez created a Folklore Study group associated with UCLA. I had read Homer in college, but had no idea that we had our own Philippine epics. We worked on transliterated manuscripts, which were actually difficult to read, but I was enchanted to learn about our own gods and goddess, of our river of the dead, something like the river Styx. Lam-ang, Agyu, Tuwaang, Meybuyan --- these epic heroes found their way into my first novel, When the Rainbow Goddess Wept.

Learning about our Philippine epics also deepened my sense of identity. It gave me a greater understand of who I was/am; and it grounded me to know I came from ancient people who had their own stories of gods and goddesses, and magic, and flight from oppression, and so on.

Ralph’s next question is :

2. How autobiographical are the characters and the plots in your short stories, especially the ones set in Ubec/Cebu, your hometown?

The first answer that pops up in my head is: No, my stories are not autobiographical at all. I make a distinction between memoir and fiction.

The truth is that many of my characters have been inspired by characters and events from Cebu where I grew up in and which I visit regularly until the pandemic broke.

I have to give you a background about my mythical place, Ubec. When I began writing stories, I used characters and real life situations from the Cebu on my youth. But I had such a difficult writing because I compelled to tell the truth. One day when I was doodling. I reversed C-E-B-U into U-B-E-C. I stared at those letters on the piece of paper and fell in love with how it looked and how it sounded. I knew then that Ubec would be my mythical setting for my stories. I should point out that this mythical setting may be something like Cebu, but I’ve changed it enough so Ubec is not Cebu.

When I stumbled upon Ubec, my writing opened up.

Suddenly I could transform the real person said to have horns, into the sensual widow Agustina in one of the first short stories, “Woman with Horns”.

Our cook Menggay became Laydan in my first novel. The girl that I had been, contributed to the characters of Remedios and Yvonne and Gemma in my stories.

You will note that I refer to the transformation of the real-live characters I had known and written about. When I am working on fictional characters, even if inspired by people I knew, I flesh them out to find out what makes them tick, what is unique about them, what their deepest conflicts are. By the time I get done with them, they are no longer the person who had inspired me. Some aspects are retained, but they have been molded or fictionalized in order for me to be able to write their stories.

There is another thing I want to mention about characters in my stories. While I sometimes create characters inspired by people whom I find interesting, there are occasions when these fictional characters come to me. They are not based on any one I know or imagine.

For instance, when I was writing “Woman with Horns”, specifically the funeral scene of the mayor’s wife, I saw the following in my imagination. Here I quote: “Near the hearse, an old man riding a horse stopped them. He was dressed in a revolutionary uniform with medals hanging on his chest, and a gun in his right hand which he fired once. Gasping, the mourners stopped still. The old man ordered the men to open the casket. He got off his horse, bent over the casket and planted a kiss on the corpse’s lips. Then he got back on his horse and galloped off.”

After finishing “Woman with Horns”, I became obsessed with who this old man was. I wondered about him: you were a soldier and you had taken great risk to present yourself at the funeral of this woman during wartime. Clearly, you had loved the Mayor’s wife. As I tried to figure out who he was and what his conflicts and motivations were, I discovered his story – his point of greatest stress – and I was able to write “The Black Man in the Forest”. Many people have told me this is one of the best of my short stories.

In a nutshell, “The Black Man in the Forest” is the story of a hardened Filipino general who while retreating with his men away from the American military in 1901 during the Philippine-American War, encounters and kills a Black American soldier. This event leads to his character change where he softens and becomes humanized.

Another character who just popped into my imagination was the young man in the story “Casa Bonita.” He was a young man who becomes obsessed with a beautiful wife of a wealthy man. His obsession leads him to committing murderer. While I was working on the story, there was this murderer talking in my head, which I found rather creepy. Fortunately he went away after the story was written.

I discovered I could even write from the point of view of a dog, Romeo. In fact, I can write about any character as long as I’m interested in that character, fascinated enough so that the character inhabits my mind as I try to figure out he or she really is and what his or her stories is.

3. How important is the setting (Ubec/Cebu, Vigan, and Acapulco) to your narratives?

To me setting is very important in storytelling. Setting is where my characters live and walk around in. It is where something happens to them externally as well as internally. My characters’ settings influence their characters and their development.

If there is World War Two happening in Ubec/Cebu, my characters have to respond. They have to physically move in that place; they have to make decisions based on the events. In the case of When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, my characters evacuated (ni-bakwit) to Mindanao. The men had to fight; the women had to live simply; they little girl has to turn to the ancient epics to make sense out of the horrors of war.

The young girl in the story “Vigan”, moves in with her grandmother’s place after her mother is widowed. Her being in Vigan is an important part of her story. Her isolation in Vigan, the antiquity of the place, her access to the mangkukulam Sylvia, are important aspects of the story. Her story would be entirely different if she had lived in California for instance instead of Vigan.

Likewise the setting of Acapulco in the story “Acapulco at Sunset” is an integral part of the story. We have a Filipina wife and mother during the time of the galleon trade, living in Acapulco, far away from her first home of Intramuros and her past, which she yearns for, and her only link to this past is the galleon. The story could not be set elsewhere. And her character and her development would be different if Maria Soledad (the character in Acapulco at Sunset) lived elsewhere.

I want to add something about my stories that relate to character and setting.

When I first started writing stories, I used Cebu/Ubec primarily as my setting because this was familiar to me, and because I wanted to explore it further in my imagination. I later I wrote stories set in Manila, Vigan, California, Spain, Peru, India, France … anywhere in fact. What was important to me was that I was interested in the characters and situation.

This ends part 1 of my talk.

PART 2

This is part 2 of my talk.

I will now answer Jack Wigley’s questions – hi, Jack, thanks for the questions:

His first question is:

1. You’ve written at least three novels and three short story collections. What was easier to write, a novel or a short story collection? What are the challenges of writing a novel? A short story collection?

The short answer is that a novel is far more difficult to write than a short story collection. Writing a novel is a huge task, a major commitment that can take years. I am referring to character-driven stories here. It can take three, four, five, six, even twenty years for some people to finish their novels. And sometimes, one can spend all that time writing a novel, only to discover it’s unpublishable.

A short story collection can be attacked bit by bit. I never really set out to write a short story collection. I write one short story at a time, as the stories enter my head, and when I have a dozen or more, then I consider collecting them into a book.

Some people say short story writing is running a sprint, while writing a novel is doing a marathon. This is true.

Sometimes I can finish the draft of a short story in one sitting. But one rarely just dashes off a novel.

For me the challenge to write a novel came about after my first short story collection was published. I felt I could write short stories with some ease and I wanted to prove to myself that I could write something long that was coherent. So I started writing When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, originally known as Song of Yvonne.

It took several years to write this novel. I do not write formula, so in many ways, the process of writing a novel is hit and miss. It’s a constant exploration in my head as to what the real story is.

So in the case of When the Rainbow Goddess Wept: The very first draft was about the time of my life in Cebu when I was around nine years old. That draft was filled with memories of my mother and me visiting her best friend who had a niece who was my own best friend – all generally pleasant memories of my childhood, and terribly boring. Nothing happened. There was no conflict, no drama.

I put aside the manuscript and was depressed for a while, but then one day we watched the movie, Hope and Glory, about a little boy in London during World War Two. Something clicked in my head: there was a connection between that story and mine.

I looked at my original draft and discovered that my characters had been giving me broad hints as to what their story was about. They always talked about the past, about the War, and what had happened to them. “Do you remember when so-and-so was killed by the Japanese in Mindanao?”

I remembered thinking: Oh my God. This is wanting to be a War Story.

And I became frightened because there is a writing rule: Write about what you know. I was born after the War; what did I know about it?

But still I could see that the characters were demanding that their real stories be told.

Finally, I metaphorically rolled up my sleeves and began. And if it was going to be a War Story, well then, so-be-it.

I had to make changes. I had to put my characters back in time, in 1941 and I stopped being me, but became Yvonne. I began right when the War broke. And like magic, the novel moved, and the pages and chapters flowed.

My other two novels were just as difficult to write. The process always felt sloppy but also magical.

The first draft of the novel Magdalena was slow and boring, even I would get sleepy reading it. I decided to turn the chapters into short stories if I could. I was doing that, cleaning up a chapter, cutting out what was unnecessary, getting to the core of things, when I I had an epiphany – the novel wanted that format. It wanted those fragmented pieces in the book! So once again, I followed the story and put together the book, which is non-linear and confuses some readers but which is beloved by academics and poets.

Same thing with the third novel. For this one, I joined the online NaNoWriMo, novel writing program, wherein you write an average of 1,667 words a day with the goal of completing 50,000 words in a month. What happens, if you want to meet the deadline is you stop thinking about the plot and so on, and just madly try to reach the word count.

In the end I had 50,000 words of, not a novel, but mish-mash. But, I had something to work on. That is where my third novel The Newspaper Widow came from. But it took several drafts and several years to get the work done.

So, yes, I have to say that writing a novel is far more difficult than writing short stories or putting together a short story collection.

You have published your first book, “Woman with Horns and Other Stories” in 1987, when you were already approaching 40 (sorry for revealing your age). Is it wise for a writer to publish his/her work when he/she is already at a “ripe” age? What are the advantages/challenges of this?

2. Jack’s question assumes that when one gets older, one might produce stronger works.

I am not sure that age has very much to do with good writing – and here I refer to character-driven stories. One needs to be clever at writing, at crafting stories, AND more importantly, one needs good stories to tell. The first part – being good at crafting stories is part gift and part learning – one can improve one’s writing skills. The second part – having good stories is dependent on how well a person can read the human heart. This sounds like a cliché, but it’s true. The strength of fiction is dependent on the complexity of the characters; a shallow writer will tend to create shallow characters; a writer with depth, maturity, empathy has a better shot at creating deep memorable characters.

I like to point out that Madame Bovary by Flaubert could have been a cheap romance novel, but for the complex characters Flaubert created.

I did not plan to hold off my writing career until I was older. My life, like my novels, seems to be non-linear. That is, it’s a bit unplanned, or more precisely, I would plan one thing, then end up doing something else.

After high school, I wanted to be a civil engineer like my father. From St. Theresa’s College, I went to Engineering school at the University of the Philippines, where my father had once been a professor. My father would have been embarrassed when I almost flunked Math. I quickly transferred to Maryknoll to take up what seemed the easiest major, Communication Arts. After graduating my Maryknoll, I went on to UCLA to take up Film Making, but discovered that making movies is a terribly expensive and collaborative effort. Meantime, I became a wife and mother, and all these explain why it wasn’t until the children were in school when I had the time and interest to take up fiction writing with some seriousness.

I don’t think there are any advantages in waiting to get published until one is older. If you can get your wonderful novel done when you are 23 (as Carson McCullers did when she completed her first novel, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter) --- then do it. Don’t wait.

3. Why do you write? Whom do you write for?

Your question about why I write is profound.

Why indeed do I write, struggle with the creation, deal with the difficulties of getting the work published? So, why do I write?

To try and address that question, I have to go back to when I started writing. I remember when I was nine and my father died, and in my childhood grief and missing him so much, I decided to write him letters. Letter writing was popular then, and we kept nice stationery, which I used, although. I have no record of those letters now. But I remember making it a point to update him of my young life. That was when I started writing.

A few years later, when I was already a teenager and in high school, my sister gave me really pretty pink lock and key diary, and I fell in love with writing in that diary, which I still have by the way. I tried to write poetry and had some flowery writing in there. Most of my writings were whiny and dramatic and written in pretentious style, but I got hooked, and continued my diary writing.

You know my journey: I went Engineering school, then film school, and then became a wife and mother, before I started writing stories. There’s the editing and publishing too, which are tied in with why I write.

I write for several reasons:

First, sometimes, the characters or situation will just latch on to my brain and I must explore them and get them down in writing. It is like an obsession that I can’t explain.

Second, sometimes, images and feelings need to be looked at and sorted out – memories for instance, and writing helps me do that.

Third, I recognize that this ability to write is a gift from the Creator, and so I plod along.

Fourth, and this is more true for the books I have edited, when I compare our Philippine or Filipino American literature with Western literature, I can see that there are gaps in ours. It may be less so now, but decades ago, there were obvious gaps to me. That was what got me started editing anthologies such as Fiction by Filipinos in America and the more recent two volumes of Growing Up Filipino, which I did when I learned that there is a scarcity of such books. I am currently working on Growing Up Filipino book 3.

The question of “whom do you write for” is tricky to answer, because on the one hand I am writing for the Filipino audience because I feel that my stories belong in the Philippines. But on the other hand, I am writing in English because that is the best way I know how to write and also because I want my work to have a wider audience.

I cannot really imagine writing in Cebuano. What are my chances of finding a literary agent? What are my chances of getting my work published in the US where I reside? It would be too complicated to have to get the work published in Cebu, and then have the work translated into English to try and catch a wider audience.

The fact also is that I have mastered the craft of writing fiction in English, and to have to relearn doing this in Cebuano would be difficult. I will tell you a story of how, during one of my visits to Cebu after years of exile here in the US during the Marcos years, I was with my nephews and nieces. We were speaking Cebuano, and I said something that made everyone pause, then laugh. I used a word that was no longer used. The word had become antiquated. The living language of Cebuano had moved on and I was stuck with words I had used decades ago.

Having said that, I want to add that I have great admiration to those who write in Cebuano or Tagalog. Many years ago, when I was in Spain representing PEN USA West, I met some Kurdish writers, and I was impressed that they produced books in their language even when they did not have a country. This is very important work which I admire greatly.

With that I will end this talk.

You can find me in social media and my official website, ceciliabrainard.com.

Thank you once again, Jing, Ralph, Jack, and all of you. Keep safe and best wishes!

#Philippineliterature #filipinoliterature #filipinobooks #filipinoauthors #Filambooks #pinoyread #Cebuanoliterature #Cebulit

No comments:

Post a Comment