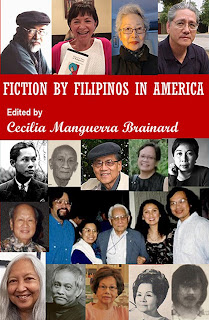

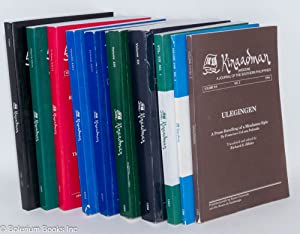

Many thanks to Dr. Erlinda Alburo for calling my attention to this academic paper about Filipino American fiction published in KINAADMAN Vol, XL, 2018 (A Jounral of Southern Philippines, published by Xavier University). The study includes discussions of stories from books I edited, including Fiction by Filipinos in America, and Growing Up Filipino 2.

Dr. Ma. Elena L. Paulma looks at the works of Amelia Bueno, Lesliann Hobayan, Rashaan Meneses, Julia Palarca, Veronica Montes, Evelina Galang, Leny Stroble, and other Filipino American authors and academics.

Thanks to Dr. Ma. Elena L. Paulma and Kinaadman for this study.

Source: Kinaadman Vol XL, 2018, All rights reserved

ARTICLES

A Locational Feminist Reading of

Filipina-American Fiction: A Non-Fiction

Ma Elena L Paulma

Abstract

This paper tackles the concept of epistemic violence described by Michel Focault and Gayatri Spivak as the erasure of cultures, languages and identities. Taking into consideration several voices, to wit: those of feminist literary theorists, characters from selected Filipina-American fiction, voices of Filipina-Americans whom the writer has had conversations with in America, the creative non-fiction voice of the writer and the writer’s own voice in weaving together this collective experience, this paper elucidates that the search for “home” is the context for the international diaspora of Filipinos. Interlacing critical analysis with creative non-fiction, the paper outlines the creation of the reterritorialized “third space.” By applying Susan Friedman’s five locational tropic patterns, namely: the metaphorics of “glocation”, migration, nation, borders and conjuncture, the paper examines seven selected short stories written by Filipina-Americans, all focusing on Filipina-American characters. The paper shows that Filipina-Americans experience a continuing sense of marginalization as they are neither entirely included in, nor completely excluded from, the American landscape.

Keywords

epistemic violence, locational feminist tropes, postcolonial, decolonization, dislocation, marginalization, lost identities

“Humpty Dumpty is a fantasy. It is fiction, not non-fiction,” pipes Joanna, her little hands clasping mine as we follow her Mom down the forest path littered with golden and orange autumn leaves.

“Fiction, like Cinderella?” I ask, holding on more tightly as she tries to traverse the uneven rocks lining the path.

“Yes, like Cinderella.”

“And what about you, are you fiction or non-fiction?” She laughed at my silly question and balancing precariously on the huge stones like a little humpty dumpty, she replied, “I am non-fiction because I am real,” with the authority of five full years of life experiences.

Joanna is a second-generation Filipina-American. Her mother, born, raised, and educated in the Philippines, migrated to the US when she married her Filipino-American husband. I am a Filipina, born, raised and educated in the Philippines, here in the US for a brief stay and writing this paper from a space common to all three of us. This is the reterritorialized “third space” created by what is known as epistemic violence, or that which erases cultures, languages, and identities. In seeking to both question the assumptions that perpetuate this violence and to affirm that which had been deleted, this paper enquires into notions of identity through the production of meanings, but of several intersecting texts: oral accounts of Filipina-Americans, my own personal experiences during my brief time here in the US, social media posts about current events in the Philippines and the US, readings on Filipina-American literature and feminist methodologies/approaches.

The main thread that runs through these interwoven texts is the Filipina-American and how her story is told by her fellow FilipinaAmericans. Filipina subjects of Filipina-American writers are described by theorists as heterogeneous and mobile, their stories dwelling upon the problems of articulation and silence, memory and history, individuality and community, responsibility and apathy, awareness and amnesia, trauma and recovery as well as the material stratifications that mark the bodies of Filipino subjects and their contingency with the world’s subjects (Sulit, "Philippine Diaspora" 147). In her discussion of transpacific femininities, Denise Cruz speaks about cultural representations and authorial strategies with reference to movement across borders, transition and change, class and gendered hierarchies, and changing imperial and national dynamics (Cruz 7-8).

Blending personal experiences with theoretical reflections, the meanings produced in this paper will be framed within Susan Friedman’s five locational feminist tropic patterns: the metaphorics of “glocation,” migration, nation, borders, and conjuncture. These five tropic patterns are the prevalent forms of geopolitical and transnational literacy.

The term “glocational” is a combination of the terms globaland local. Grewal and Kaplan argue for a form of transnational feminism that avoids the homogenizing tendencies of global feminism, respects the material and cultural specificities of local feminist formations, and encourages analysis of how the gender/race/class system in one location is politically and economically linked to that of another (Friedman 30). Transnational and postcolonial feminists address gender and human rights issues by considering cultural values, religions, economic conditions and class issues, national histories, systems of government, health practices, colonial experiences, and culturally defined gender roles (Tong). Thinking glocationally involves understanding how the local, the private, and the domestic are constituted in relation to global systems, and conversely, how such systems must be read for their particular locational inflection (Friedman 30).

The international diaspora of Filipinos, generally understood as an effect of the economic condition of the Philippines, can also be seen as a result of colonialism/imperialism in the historical context, the negation of the Filipino by the master’s narratives accounting for the displacement of self (Strobel 29). “To be is to be like the master” elucidates Leny Strobel as she explains that our colonized consciousness has convinced us that to be Filipino is not enough. One effect of this internalization of the dark shadows projected by the colonizer onto the colonized is the desire to live in the master’s house (Strobel 29). A manifestation of this desire is “marrying out” (or marrying up means marrying white) of an economic caste, out of an institutional, internalized, colonial sense of inferiority, and out of the Philippines (Pierce 35). The most stark and depressing legacy of colonization as a patriarchal legacy is the exploitation of women, the colonized taking care of the colonizer ironically played out in hospitals by Filipino nurses (Strobel 29). Migrant women are “deskilled,” low-paid, limited in their access to particular jobs and social rights, exploited and harassed, and their gendered and ethnic vulnerability enhanced (Erel 241).

Linda Pierce speaks of the perpetuation of the colonial complex through a denial of one’s internalized oppression. Because it is global, deconstructing the systematic, imperial whitewashing is difficult. It is therefore necessary to counter the panoptic, outside gaze with an oppositional gaze or gazes of resistance by stepping away from denial and breaking the silence (Pierce 42).

Postmodernist thought scrutinizes dominant (hegemonic) knowledge claims and associated binary categories. It questions assumptions of “truth” and “self ” as stable (or essential), ahistorical, or universal, and stipulates that reality and identity are socially constructed, embedded in relationships and historical contexts, and reproduced through language and power relationships (Bohan; Morrow). The view of history as a collection of objective facts is no longer viable in current academic discussions, because the writer of history will always perceive events from a particular position and with a particular bias. Knowledge, rather than being objective and neutral, is a construct of the greater global context involving politics and economics. These postmodernist perspectives, which counter the perpetuation of colonial mentality, still escape a majority of Filipinos.

What Michel Focault and Gayatri Spivak call the “epistemic

5Vol. XL

violence” of cultural/gender marginalization and identity crises continue to be relevant.

“Being a Filipina-American means being postcolonial — after colonization, but certainly not over colonization,” states Leny Mendoza Strobel, who considers this a necessary phase in the development of a healthy Filipino-American cultural identity in the United States. For a “Pinay” living in America, there is an automatic relationship to decolonization whether active or passive, engaged, conflicted, opposed, or in denial. It is about being aware of one’s “Philipine-ness” in America, the persistent obstacles faced by one’s family, and one’s relationship with others. To decolonize, one must ask: Where do I go from here? (Strobel 32).

The “migration” rhetoric reflects the meanings of immigration, the constant travel back and forth, and diaspora for spatial modes of thinking about identity. “As the body moves through space, crossing borders of all kinds, identity acquires sedimented and palimpsestic layers, each of which exerts some influence on the other layers and on identity as a whole” (Friedman 28).

Place and movement are basic concepts in both my research approach and my personal experiences as a scholar here in the US. I was able to hitch a long ride, first to New Orleans, and in another trip, to New York, all the way from Chicago. In both these rides, I listened to the stories of a Muslim princess from Mindanao who had sought political asylum in America, a retired Filipina-American accountant actively helping out newly immigrated Filipinas (specifically the ones who married Americans and encountered the usual “problems”), and a divorced Filipina-American nurse married to a Filipino. From their stories and my own sense of moving from place to place, I resonate with the words of Melinda de Jesus in her introduction to her book, Pinay Power: “We’re travelling — our presence is erased as soon as it is made.” She connected this sense of motion and simultaneous erasure to her family’s history — how they live in the very American “perpetual present,” eschewing any link to their Filipino past: “So this is the American dream — living in the perpetual present, moving through life without a past, swallowed whole, invisible, but unable to deny the lingering ache of absence” (De Jesus 2).

Friedman describes the discourse of “nation” as emerging out 6 A Locational Feminist Reading of Filipina-American Fiction:

of the impact of colonialism and postcolonialism, resonating with geo-political state to state relations in an international context (26). The rhetoric of nation can be located in spaces that are “home” to the characters: their own bodies, their families, and communities. Their words reveal their perception of themselves as women of their class, educational background, race, and ethnicity.

In November 2016, scores of Martial Law human rights victims, their supporters, and millennials took to the streets in protest of the surreptitious burial of Ferdinand Marcos, the Philippine dictator who had ruled for 20 years, at the Libingan ng Bayan (Cemetery for Heroes). This burial was sanctioned by the same Supreme Court, which had, ironically, decided a case in favor of the claims for recompense by the same human rights victims now calling for justice and protesting against this revision of history. The current president, Rodrigo Duterte, was the one who instigated and approved the burial. He has become known for his “jokes” about how he should have been the first to rape a missionary who was gang-raped at a prison in his previous bulwark, Davao City. He has made jests about how he slaps the rumps of his female security agents. The saddest thing is the laughter of his supporters.

Already, the ‘home’ that Filipina-Americans speak of and long for contains a history that serves as the base of their multiple-layered identities. Diaspora consciousness places the discourse of ‘home’ and dispersion in creative tension, critiques discourses of fixed origins, and allows for borderland rhetorics that move beyond the binary to a named third space of ambiguity and even contradiction (Budgeon 283).

“We are not only born split, but we are also born on the border,” states Leny Strobel (27). “Border”rhetorics reveal spaces of desire for connection, utopian longing, and the blending of differences. Among the struggles that diasporic individuals must go through as a result of their dislocation are an abiding sense of nostalgia and the pressures of the (cultural) traditions of their homeland warring with the sense of liberation born of this very dislocation from these traditional constraints (Bose 164). “Border” experiences highlight the paradoxical processes of connection and separation and are porous sites of intercultural mixing, cultural hybridization, and creolization. Identity ensures clashing differences and fixed limits (Friedman 27).

In their discussion of literary voices in Asian diaspora, Begoña Simal and Elisabetta Marino write about recurring ideas of displacement and inscription, among other complications of the diaspora stemming from diasporic realities, be it “first” migratory Asian diaspora, or the subsequent multifarious diasporas (Simal and Marino 18). “Instead of trying to fit ourselves somewhere between black and white, we need to create a place for ourselves outside the continuum,” states Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales (139).

Filipina-Americans are “invisible” or underrepresented in AsianAmerican, Filipino-American and feminist studies. Yen Le Espiritu observes that the anti-racism agenda has homogenized differences among Asian-Americans, causing the erasure of specific FilipinaAmerican experiences and concerns. She asks this question: “Why have we Filipinas silenced ourselves? And what/whom does our silence, our self-erasure, serve?” (qtd in De Jesus 4).

In her book, “Coming Full Circle,” Leny Mendoza Strobel suggests that to decolonize is to tell and write one’s story, that in the telling and writing, others may be encouraged to tell their own (Pierce 31). The breaking of this silence, this telling of stories, or the question of the representation of Filipina-Americans carries interlaced issues and contentions, all of which suggest the perpetuation of the ethnic, gendered and racial oppression of Filipina-Americans: narratives of victimization, glossing the history of the US-Philippines confrontation, elite Filipino and Filipina authors representing stereotypes of the native Filipina, and the consumerist commodification of “ethnic literature" and “the Filipina,” the downplaying of gendered racism.

Strobel speaks of decolonization as both personal and political. One must be able to name one’s internalized oppression, shame, inferiority, confusion, anger, to reclaim memory at the personal level in order to engage in the process of creating a collective memory of a people’s history (Pierce 39). Writing is an act of surviving, listening an act of witnessing, and the reading and interpretation all part of a repetitive process of reevaluation, reconstruction, retransformation, re-transgression, and especially, relove for one another (TintiangcoCubales 140).

The antidote or the solution potentially lies in language — storytelling itself through the works of the Philippine diaspora (Sulit Philippine Diaspora, 126). The diasporic visions of Filipina-American writers allow for multiple identifications for their characters and, in turn, their readers and language assumes a transformative power that enables resistance against the perpetuation of trauma (Sulit Philippine Diaspora, 147).

The term “conjuncturalism” refers to juxtapositions of different cultural formations, replacing conventional comparison/contrast analysis of similarities and differences. This epistemological juncture sheds light on each formation and for the way in which each discursive system interrupts the other. It corresponds with the term cultural parataxis, a form of conjuncture or superimposition developed particularly as a part of modernist poetics to describe the radical juxtapositions that poets and artists made with a deliberate suppression of explicit connection. The two forms of parataxis are collage and montage. The reader/critic is invited to establish the connection not explicitly expressed by the artist or poet (Friedman 31).

This paper is a conversation among several voices: the academic voices of feminist literary theorists, the voices of the characters in the Filipina-American fiction pieces I have chosen, the voices of the women I have conversed with across the country, my creative non-fiction voice, and my voice as the writer weaving all these together to form this one text. This deliberate mix comes from an awareness that researchers are not abstractions but are positioned within specific political, social and cultural contexts, which in turn influence what they perceive (Eliassi 86). The blending of academic research approaches with experiences and reflection through the mechanism of creative non-fiction grounds issues in lived experiences (Arvanitakis 9-10).

Ulrika Dahl speaks of dialogues with women around kitchen tables and on car rides, particularly those that narrate diasporic stories and migratory memories and memoirs as (feminist) storytelling practices because in their situated and embodied forms, stories help us create other knowledge-worlds (150-154). I was able to converse with Filipina Americans from varying societal positions and ages during two long cross-state car rides, two hop-on hop-off bus rides, several train rides,

9Vol. XL

approximately ten plane rides, and multiple walks along dark city streets lined with trash, along manicured suburban lawns, forest paths lined with trees, and make-believe cities peopled with Disney characters. Their stories, their voices will be intertwined with mine.

The spatial rhetorics of glocation, migration, nation, borders, and conjuncturalism identified in the chosen literary texts will be discussed in this paper. Rhetoric, states Susan Freidman, provides access to the underlying categories of thought which would otherwise remain lost to consciousness. In short, rhetoric points to ways of thinking (Friedman 17). The presence of the tropes indicate thought processes, which counter those (e.g., binaries, essentialism, linear development, universality) that perpetuate the colonization of the mind, bringing to light the multiple inscriptions that cultural categories such as race, gender, ethnicity, and class make on individuals. The above concepts made me choose to write about diasporic short stories written by Filipina-Americans about Filipina-American protagonists.

“Perla and Her Lovely Barbie” by Amalia B. Bueno(Brainard 2739) is set in Hawaiiand narrated by an unnamed teenage Filipina who is the middle child of three sisters. This linear-plot story revolves around the image of the Barbie Doll which is well-known, well-loved, and wellsold to young girls all over the globe.

The main character is 12 years old, hovering between childhood and adulthood. In Filipino families, age defines one’s authority. Her border (age/generation) position allows her to have a measure of authority over her younger sister, yet places her beneath her more “powerful” elder sister, Marina. She moves within two cultures: one dominated by Mcdonald’s and Barbie dolls; and the other one by tobacco leaves, nineday funerals, and the Virgin Mary.

The trope of “nation,” which defines through the body one’s sense of self, is revealed in the very first lines of the story: “I never loved Barbie when I was her age. I didn’t even like Barbie. She doesn’t look real to me. Her big blue eyes so empty and cold scared me. I didn’t like Barbie’s skinny legs, too. They reminded me of how short and ugly my brown legs are. In fact, nobody in my family looks like Barbie.” A woman’s body is her first home. Her self-image is reflected in the way she describes her own body.This young girl becomes aware of her “difference” (and inferiority) as early as her 12th year.

Toni Morrison speaks of “the damaging internalization of assumptions of immutable inferiority originating in an outside gaze.” It is an “outside gaze” that made us learn to privilege whiteness (qtd in Pierce 39). Through her words, we sense the main character’s desire to break away from accepted (hegemonic) superior standards of beauty. Her learning about her own “ugliness” compared to Barbie look-alikes such as schoolmate Elizabeth (Lizby) Watson has been slow and painful. This lesson was brought home to her by her best friend Jason who turns away from her when she tells him that Lizby “type of gecko lives in Kalihi Valley and plays the flute in the summer” looks just like a stiff Barbie doll. He takes up with Lizby, and she takes it upon herself to destroy her little sister Perla’s favorite Barbie doll.

Perhaps she desires to spare her sister from the same rejection, especially when she notices this: “Perla was starting to act more and more like Marina. Like wanting to wear dresses instead of pants and eating less and smiling more. Perla also didn’t want to go outside and play in the sun as much, because she didn’t want to get her skin darker. Just like Marina, who always put on sunscreen and wore a hat even if it wasn’t sunny outside.” She suggests that they give the Barbie doll a hot bath from water boiled in a pot, “to see if Barbie’s skin would slowly get soft or if it would melt right away.” But Perla refuses to oblige.

She tries to convince Perla by suggesting that they play at having funeral rites, first with items from the garbage can, and then later with the Barbie doll. This playful funeral rite becomes a mix of Filipino and American cultures, creating a parody of that which is considered as sacred: “I said the Filipino version three times, then the mixed English version three times. I ended with, ‘Mother Mary, you are full of bitter melon’ and pushed the cross in at the far end where the chicken’s head was buried.”

Perla finally concedes when her sister suggests something, which approximates a funeral rite familiar to Filipinos: “So I said we could dig Barbie up nine nights later. I could tell Perla was thinking about it. So, I said, as a bonus, on the tenth day we could pretend that one whole year had gone by and we could have a one-year death anniversary party for Barbie.” Filipinos adhere to a nine-day novena prayer after the death of a loved one, and honors the death anniversary every year.

This conjunctional trope of juxtaposing play with the serious theme of death, of making parallels between what is considered as trash and what is considered as valuable, of what is real and imagined is highlighted by the protagonist: “I told her, Perla Conchita Domingo Asuncion, you said so yourself that you do real things to Barbie, like feed her, and sing to her and comb her hair. Well, I explained, another real thing that happens is people go away and people die. We could practice burying Barbie as just another real thing that people do. We could pretend Barbie died, say a Mass for her and then bury her.”

It is interesting to note that this final death, this burial of the Barbie doll, is accompanied by items collected (not necessarily with their permission) from all the members of the family. Perhaps it is the main character’s desire to save not just herself but her whole family from the pain and confusion of being her “brown and small” self.

The story ends with these words: “Perla was disappointed that Barbie did not seem that pretty anymore. And her beautiful clothes were a little dirty. After not playing with Barbie for more than a week, she didn’t seem to miss her as much as she thought she would. Now she mostly puts Barbie up on the shelf by her bed. Perla takes Barbie down once in a while to let Barbie sit quietly next to her. I knew she would end up not loving Barbie so much.”

Perhaps the Barbie can never be buried, no matter how dirty it becomes or how old. It will always be there, staring from an imagined chair next to any Filipina sitting before a mirror, the white faced, longlegged superior self to which she will always be “inferior.” However, the very act of burying also signifies a certain death, for the main character at least, and now for her sister.

In “Double Dutch” by Lesliann Hobayan (Brainard 42-49), a double-named girl skips to a double-roped game, after which she goes home to her double-cultured family. What happens within the home forces her to make a painful choice. The feeling of being “left out” makes her want to “fit in” so that she must “leave out” what is not “in.”

Many Filipinas are given two names, the first of which is often “Maria,” an inheritance from the Spanish colonizers of the Philippines who replaced the pagan practices with the Catholic religion. Many of 12 A Locational Feminist Reading of Filipina-American Fiction:

us still carry this definitive mark as it is handed down from generation to generation. At a recent international gathering, I was with a fellow Filipina and both of us were addressed by our first names, Maria. We had to correct the other participants and tell them that we were called by our second names.

Our protagonist hates the fact that her parents gave her two first names, the fact that her middle name is her mother’s maiden name: “It sounds so strange. Maria Elizabeth Rañola Ramos. Two first names and two last names." "But that’s what Filipinos do," her mother explained. In something as simple as our names, we carry the burden of our colonized history.

Maria Elizabeth also bears the burden of her race. “Her nun teachers are impressed with her consistent A’s, but they say it’s because she’s Asian — she’s supposed to be studious and dedicated.” Wherever I went in the US, I would hear about Filipino children excelling, mostly in school or in the field of music. This can be seen as an unconscious reaction to an unspoken sense of inferiority based on race, felt implicitly but never spoken of explicitly.

While the girls are at play, their conversations reveal their compliance with the hegemonic standards of beauty: “When I grow up, I wanna be a model. Oh yeah? Keep dreamin ‘cause you ain’t skinny enough for that.”

How does Maria Elizabeth perceive herself through her name (history), race, and body? On this trope of “nation,” she constantly finds herself “different,” always at the borders.

While Elizabeth struggles with all these tensions in the outside world, inside her home, she must listen to her parents who themselves are striving to resolve these internal border conflicts arising from their migration experience. When she arrives home, she calls to her Mom excitedly, but her Mom scolds her: “‘Ma’? What is this ‘Ma’? Who are you talking to? I am your Mommy. Don’t ever talk like that again, hah?” Elizabeth had mimicked her (black) friend Alicia when she called her mother “Ma.” This would be the first indication in the story that the parents wanted to “fit in” to eradicate anything that sounded “different” or Filipino.

Her friend Alicia had braided her black hair before she went home. She is met by these words: “What’s the matter with you? Why do you want that hairstyle? Are you trying to be Black?” In the parents’ desire to belong, to “become white,” they must eschew all relations to those considered as “other,” even if (and maybe especially because) they themselves fall under that same category. “I don’t want you playing with that Black girl anymore,” Elizabeth’s father commands.

Elizabeth starts to protest but is immediately silenced by her parents. “Soon, because the silence is uncomfortable, her mother begins to speak to her father in Tagalog, asking him about his day at the hospital, if he had any new patients. This is not a conversation meant for her.” This silencing, this marginalization through language is a common experience among second generation Filipino-American children. One can say that this border experience with language is a repercussion of what the parents themselves experience outside the walls of their home. Elizabeth recalls an incident at the store when her mother is trying to buy ox tail. “The man talked loudly and slowly to her mother, as if she were deaf. Whaaaat do youuuuu neeeeeed? She noticed her mother’s voice drop when she repeated her request. Then, her mother grabbed Maria Elizabeth’s hand and they left the store quickly. They never did get the ox tail.”

This is how Filipina-Americans are silenced, how they erase themselves, how they build their inner walls: “She forces herself to finish what is on her plate so she can be invisible. A clean plate grants permission to leave the table, to disappear. So she does. The next day, she doesn’t tell her school friends about Double Dutch, doesn’t mention the spiraling ropes, the dancing. Nothing. She says nothing all day. Walking home from the bus stop, she tries to avoid Alicia. Her walk picks up into a sprint. She looks away from Alicia’s house as she races past. For a long time, Maria Elizabeth stays inside the little white house with red shutters, watches TV, says nothing.”

The song that is sung as Elizabeth jumps between the two ropes of the Double Dutch game captures what Filipina girls grow up with and how they come to know themselves:

“We can’t tell you where it started

We don’t know where it’s been

But have no doubt, the word is out

Double Dutch is in.”

“Here In the States”by Rashaan Meneses (Brainard 51-66)is narrated by Alma, the eldest of three siblings, the only one who has known what it’s like to live and grow up in the Philippines. Perhaps to pursue the American Dream, her parents brought her from their hometown of Cebu to the USA. The story opens with Alma’s mother calling her to help with her younger sibling who has peed in his pants. While she hides from her mother to avoid the smelly chore, these are her thoughts:“Ever since we moved to the States, I’ve had to look after my brother and sister, clean their messes, cook their food — do everything! Back in the Philippines, our house was tidier. The meals weren’t burned at the edges or left frozen in the middle. Our housekeeper, Amalia, would cook breakfast, merienda and dinner. Now we’re even lucky if Nanay comes home in time to make something. Usually I end up having to and I hate cooking.”

Clearly, the migration from the Philippines to America has resulted in a border experience of longing for “home,” for what used to be. She may have physically moved across oceans, but much of who she was remains with her as she says: “This wasn’t at all what I thought it’d be like when we came here.” Perhaps she herself was told about the American Dream. Perhaps she believed it. In this story, we see an unravelling of what she had been made to expect.

The disillusionment is drawn out in the story from the eyes of a daughter looking at her mother: “In this picture, Nanay stands proudly next to some men she worked with; everyone’s dressed in fancy suits. All these professors used to come over on weekends and holidays for formal dinner parties that Nanay liked to host. Nanay’s face was young and fresh then. She didn’t have any of the worry wrinkles she has now. I have to look away ‘cause Nanay’s face then doesn’t match what I see today. She wears tennis shoes to work now instead of those shiny pumps she used to always buy.”

A mother is a daughter’s “home,” a reflection of herself, or she is a reflection of who or what her mother has become. From where she is, in her new home but wanting to go back to her old home, she directs her anger at her Mom: “I feel like kicking something but I can’t. Instead, I say, ‘I’m not supposed to take care of Nita and Frankie all the time. You’re the mom, you should do it.’”

She leaves for a school field trip to the LA Museum. In the bus, two of her Filipino classmates tease her: “Whatsa matter, Alma, you on your period?” To exacerbate her sense of marginalization, these boys make fun of an intimate and private female ritual, their seemingly harmless taunt a possible forewarning of what awaits her in the future as a female.

She sits with her best friend, June, who is also a Filipina. “Her dad was an artist and made a lot of money back in Manila. Here in the States, he works as a cashier at Vons.” As the story progresses, it becomes clear that these two come from economically stable families in the Philippines. When they reach a street lined with huge mansions, Alma thinks: “But it’s not like June and I haven’t seen mansions like this before. It’s not like we never lived in our own back home. We both turn to the front of the bus and stare at the road ahead of us. I know what June’s thinking but she doesn’t say anything. We never do anymore.” Once more, the loss of voices, the seeming disappearance of truth as expectations are turned upside down.

The migration experience of these girls has been an awakening. The realities of what they thought would be a better place, a better life has come to this: “Life in the States has been smaller and grungier compared to what we used to have. In Cebu, we had a swimming pool in the backyard and a jet stream bathtub that could fit three people.”

The trip to the museum changes Alma, not because of the Modigliani paintings, but because of a sight she could not forget. Outside one of the mansions, she sees her mother. But she does not point her out to June or call out to her Nanay. She silences herself, but it is a silence that screams inside her: “I keep wondering where Nanay is and what she’s doing. I know she’s out there somewhere cleaning Amy and that baby’s mess. I take a deep breath but my insides are burning. I wish I was home right now with Nanay telling me to put away the dishes or do my homework. I wish I was with Nanay on that walk instead of Amy. I feel raw like a pumpkin that has all its seeds and pulp scraped out. I can’t shake how that little girl pulled my nanay’s arm and the look in my nanay’s eyes.”

When her mother comes home from work, Alma breaks her silence and finally asks: “Is this what you thought it would be?” Her mother gives her a kiss and says, “I’m not sure what I thought.” Such is a border statement that speaks of what was and what is. This reconciliation between mother and daughter is strangely brought about by the daughter’s finally seeing with her own eyes what this new place has made of her mother, what this new space has made of her as a daughter. Their longing had brought them here, and they remain in this space of longing.

“In America, Restaurants Are Crowded” by Julia Palarca (Brainard 317-324) is a snippet from the life of a Filipina, born and raised in the Philippines, who goes to America to study. Migration brings her to the border spaces where she must learn to relinquish old for new perceptions about what she longs for and how she knows herself.

The trope of “nation” is immediately evident in the very first words referring to the main character: “The brown slant-eyed girl smiled…” The objective voice with which this story is written serves as the “gaze” that identifies the woman as “different.”

Migration is an act that is born of a deep longing. Imaged as the empire and the center, the source of hegemonic culture, America is everybody’s dream. Antonia (Toni) was sent off by her parents, her mother’s eyes “filled with a loneliness more poignant then tears,” her father “carried Pride like a flag.”

The lone waitress who is at the sink glances at her and continues to wash the dishes. The brown girl looks around “with amused understanding” and in her thoughts: “I know, I know.” In the story, the character does not articulate what she knows, but as readers we understand that what happens in the restaurant must have been happening to her for a while. Any FilipinoAmerican reader will probably also know where her words are coming from. Even now, in this postmodern era, I still hear stories about Filipinos being served last in restaurants: “In America, restaurants are crowded. Ages before one is served.” I have also spoken to Filipino-Americans who do not at all experience racist discrimination, but I have also spoken to those who have.

There is only one other customer seated beside Toni. When she removes her coat, “her arms looked fragile and dark beside the hairy whiteness” of the man seated next to her and self-consciously draws away from him. In a glocational sense, this self-consciousness, this almost reflexive “moving away” is among the small, specific acts that articulates in minute detail a global history involving politics and economics.

She waits and smiles until “the bright smile stiffened into an impaled curve on her mouth.” The waitress continues to ignore her and Toni feels her cheeks burn: “Twenty million little pins pricked her face, first on the forehead, then ran in a pitted path down to her chin. Oh, please, Lord, don’t let it show.” What does she not want to show and why is she afraid not to show “it”? The story’s silence about her reaction mirrors the way she tries to erase herself.

The man sitting next to her is looking uncomfortable. She breaks her silence: “Don’t they serve foreigners here?” and the man calls out in anger, “Hey! Come on over, will ya? ”

When in the border space of longing, one often steals away from reality towards imagination. Toni finds herself having a conversation with the stranger next to her. He becomes a student like her, a German Jew whose words come out “like a rush of angry waters, bitter with pain: ‘What a rotten thing to do! Don’t ever, ever allow anyone to treat you like a lesser human being. Least of all, not an arrogant, stupid waitress.’” He asks her out, and offers to take her home. But the reader, along with Toni, is made to realize that the conversation occurs only in her mind. Toni must come back to reality, to the coffee and macaroni and cheese, which she had waited for but no longer wants to eat.

In“Apollo & Junior Grow Up” by Veronica Montes (171-176), the unnamed first-person voice is that of a mother and wife. The narrative revolves around her son and her husband, her life story and identity seemingly revolving around theirs.

“In the collective consciousness of Filipinos, dislocation is assumed to be a natural state. We have learned not to take our identity crises seriously. We have learned instead to laugh, and sing, and dance, for it seems that these are the only permissible ways of asserting an identity” (Strobel 25). The story opens with her son saying, “As a Filipino, I feel it is my responsibility to be a good dancer.” This single statement will not often be heard from Filipino-Americans, especially 3rd-generation teenagers whose parents can no longer speak Tagalog or will not know much about the Philippines. Once I asked Filipina-Americans who had been born here, “How do you think of yourself — Filipino or American.” The swift answer was “American!”

As the story unfolds, the reader will learn that, as with many other Filipino-Amercian households, it is the grandparents who hold the family’s/nation’s stories. Perhaps this is also where this teenager has gotten his sense of being Filipino, even wanting to be Filipino and feeling “responsible” for promoting his culture. Apollo stays awake until two o’clock in the morning to watch the “hilarious splendor” of Filipino variety shows. The mother, caught between these two generations, embodies the border longing for the loss of the past. Her lack of interest in her family’s past or in that “other” nation’s history is in stark contrast to her son’s constantly asking her to teach him Tagalog, to tell him about the persons in the collection of pictures she keeps. His questions are merely “a gentler reminder that the things (she) never bothered to learn could have made him happier.” Her response to him is always: “You know I don’t know.” Sometimes, she would make up stories: “I tell him about imaginary gamblers and doomed love, about an illegitimate baby girl who became the legendary beauty of Pasay, about a boy with no tongue.” In a conjunctural sense, these made-up stories somehow bear a hint of truths she keeps from her son – about doomed love, illegitimacy, and the silence that pervades her life.

It is her son who tells her about her grandfather, who was one of the five illegitimate sons of a married Spaniard and a Filipina with a beautiful voice. The Spaniard had seduced but never married the Filipina, a common enough story for Spanish-colonized Philippines. Perhaps this is the reason behind the mother’s silence. This unspoken shame surrounding children born out of wedlock and the woman’s burden carries over to her own story. She and her husband Jun had gotten married at the City hall, her Lolabreathing, “‘Thank God Thank God’ as if the five-minute legal proceeding had washed (them) free of sin.” She knows that her husband stays with her “because (they’ve) been together for more than half our lives, and he can’t think of what else to do. Leaving (her) would be like abandoning his only sister.”

“Didn’t you want to know?” her son asks. And she replies, “Sometimes. No, not really.” In this border space which she occupies, nothing seems to be happening, nothing has happened, and nothing will happen. When her son queries, “But Ma, how can you know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been?” She replies, “Where I’ve been? I’ve never been anywhere but here,” deflecting her son’s reference to “her people” and saying: “You and your dad are my peeps.” This voice presents itself as devoid of any self without her son and her husband: “The difference between us is that he wants to know the stories, while it’s enough for me to just look.”

This peripheral observer position is also evident when she tells the story and her husband who is having an affair (one among many): “My husband knows that I’ll just wait until this girl and her nice smell goes away.” She states that “Junior is bored with her face” and that she felt the same way about him when she was 14. Yet her seemingly indifferent reaction is belied by her inner thoughts when Junior says to him, she has become a “minivan,” and had stopped being a “sportscar.” Her thoughts, her actions, the images she uses for this moment are conjunctural: “I turn my head away and think of a dozen ways to answer him. My tongue starts to bleed, I’m biting so hard. But I don’t say a word because once you do, you can’t take it back. It just twists in the wind like a capiz shell mobile, gathering dust.” There is both anger and silence, movement and stillness, the image of the thin capiz shells revealing fragility, the gathering of dust an indication of neglect.

“I see that he can hardly breathe. I see that.” This is how the wife sees her husband and in her recognition that “these things never work out,” is a sense of resignation, a giving up on her own life. She, too, can hardly breathe. Sometimes, however, she leaves her middle ground, and breaks her self-imposed silence, as when she shows her anger to her husband: “Is that what you do? You handle us?” In her thoughts she admits this, when her husband throws the forks and spoons which clatter onto the floor: “Sometimes — I pick up a fork — just sometimes — I pick up a fork — I hate Junior.”

Apollo asks her one day if he was a mistake like his Dad had said or if she had done it on purpose, becoming pregnant. She just says his baby name, “Po.” Her son says, “I won’t tell him.” We finally learn why she stays: “When Junior walks out of any room — nothing fills the space. Not music, not food, not even my son.” She hates him, and she loves him. She wants to go, she wants to stay. Junior has taught her how to drive and is buying her a new car, even though she does not want to.

When Apollo asks her that he be allowed to drive, he throws himself into her arms: “He’s done this forever, but I can’t stand it now. I’m scared I will hold him for too long and he will shrink from my desperation and walk away and never stop.”

She is the link to the past which her son longs for, and she stands on the brink of an end in a marriage. The last scene is that of her son and husband driving away from her. They are growing up, growing away from her. She sits waiting for them to come back, in that border space where desire intersects with indifference, where love is mingled with hate. Perhaps she recognizes in her own son her own need to know her past, so that she would know where to go.

Migration is the driving trope in Her Wild American Self by Evelina Galang (67-82). “When Mona and Ricardo moved to America, they brought with them a trunk full of ideas — land of opportunity, home of democracy and equality…but God forbid we should ever be like those Americans — loose, loud-mouthed, disrespectful children.” Thus was the border stage is set for their daughter, Augustina, brought to America, the land of the “free,” and expected to uphold Filipino values, beliefs, and traditions.

“It’s like my family’s stuck somewhere in the Philippine Islands.” This is the first statement of the voice, two generations removed, that tells the story of wild Tita Augustina “who never learned to obey, never listened.”

When she was young, Augustina wanted to be “chosen,” and wanted to carry the crucifix down the aisle. When her mother does not give her permission to do so, she stops going to Mass altogether. The word “chosen” becomes this conjunctural mix of religious belief and a desire to be “seen.” Already, a sense of being “erased” after being uprooted must have been felt by the young girl. Even when her father forced her to dress up and drive with them to church, she stayed in the car, so they finally let her stay home, but not without the guilt she must bear for burdening her mother who cries: “How will this look? My own daughter missing Sunday Mass. People will talk.” Augustina would, if they allowed her to be an altar girl and wanted to play baseball, but that was worse than not going to Mass. The unspoken assumption here is that, at that time, there were altar boys but no altar girls.

They send her to an all-girl Catholic school to tame her. On the first day of school, she gets her first taste of what it means to be “different.” She joins a group of girls with “milk-white” faces at the canteen, but they turn away when she tries to talk to them, saying: “This school’s getting cramped.” She begs her Mom to transfer her to another school but she is told it is “the best.” Her mother still believes in their dream of this new “home” as a land of democracy and equality.

Stuck between her parents’ dream and her own reality, Augustina started hanging out with her cousin Gabriel in places they’d find disturbing. “In many of the photos, her image is like a ghost’s.” Unable to find herself in both family (home) and school, Augustina withdraws into a world of her own — in the cemetery where she becomes a ghost suspended between the real and the imagined. She sits at the foot of the statue of St. Bernadette who was visited by the Virgin and whom everybody thought had gone crazy but “Bernadette didn’t give a fuck what they thought.” At school, the nuns speak about cultures, strive to keep the girls chaste and “Augustina envisioned a large needle and thread stitching its way around the world, gathering young girls’ innocence into the cave of their bodies, holding it there like the stuffing in a Thanksgiving turkey.” On her body, she wears her border “self ”: elephant-leg hiphuggers, moccasin-fringed vests and midriff tops, loose beads, and bangle earrings. Border thoughts can be articulated in conjunctural layers of east and west, religion and cult, self and non-self.

It was rumored that her cousin Gabriel was in love with her, and that he was what made her wild. Such a story may have been more acceptable than the story of her being unable to find a “home” in the institutions where she was supposed to belong: at home and in school.

The rhetorics of glocation, nation, migration, and border are evident in this scene: “She told her Mom how the nuns pointed her out in class, saying things like, ‘Thanks be to God Augustina, the Church risked life and limb to save your people, civilize them. Thank God, there were the Spanish and later the Americans.’ All her mother said was, ‘She meant well, hija. Be patient.’” Thus is Augustina locally interpellated by global events leading to their migration as a family and to her present marginal position.

The erasure and the silence continue. When she was 16, that age when one must leave childhood and move towards adulthood, Tina locked the door of her bedroom and hid away from everyone. Inside, a conjunctural mix of things affords her solace: a Western song about “Mother Mary and troubled times and letting it go, or was that be,” an altar of rocks from Montroe beach, Gabriel’s photos, a medallion of the Virgin Mary stolen from her Mom.

For Augustina, her warning was the story of Emmy, the one who got pregnant and became an outcast: “Better not be wild, better not embarrass the family like that girl.” The story goes that Augustina was sent back to the Philippines, presumably to have a baby, or to discipline her wild American self. The storyteller (the voice) telling Augustina’s story is warned by her Lola Mona and her mother: “You’re next. Watch out.”

The narrative ends with her Tita Ina giving her the necklace with its Virgin Mary pendant: “The paint was fading and chipping from its sky blue center, but still there was something about Her, the way Her skirts seemed to flow, the way Her body was sculpted into miniature curves, the way the tiny rosary was etched onto metal plate.” Perhaps it was the Virgin Mary’s purity that called to Augustina and the Emmy — a purity that spoke of being honest to oneself, of being true despite the many ways by which they were identified by the world around them. Perhaps another story will be told to the next generations — that of the storyteller who had “the same look in the eye, the same stubbornness.” Perhaps she will finally see what to watch out for.

In “Wilmington”by Gina Apostol (19-35), the narrator is the younger daughter of the woman whose story is being told. As if these were told around a kitchen table with interruptions in between words, we piece together a border story about a Filipina who socks a GI Joe in the face, and whose husband introduces his children to the parents of his other woman.

In a conjunctural palimpsest of images, memory, imagination, identity, and space, this narrative follows the migration of a mother, and two daughters from America to the Philippines and back: “The unfolding Polaroid picture was a creeping alchemical weeping, slowly blatant as migration, a movement from one place to another, the distance magically immeasurable despite the vast evident change: the liquid blankness has become all color — yellow-swirled TV tray, jester lozenges in jeans, Pookie’s blondness, my own bright eyes in Polaroid: red eyes.”

The “eyes” which see, the voice who speaks, is that of the younger daughter. It opens with images of linoleum floors and cheap faux Tiffany lamps bought at Sears. “It’s the America she brought back home with her.” These migration images are faithfully captured in a new polaroid camera, bought by the money Father wanted to save — for the casinos. “Mother was fierce: she wanted pictures.” Her family at home was starved for images, sights of the America she was seeing.

She is living the American dream. This is the story she would like to tell. But as with all border experiences of Filipinas living in America, there is another side to the story. Mother worked at the bank, wore all those exotic multinational guises. “Vietnamese? Persian? AfroScandinavian?” the customer at the bank questions her, the story a legend in the family. One didn’t need a Polaroid for people at home to recognize him. They’d call him Joe. When he learned she was Filipina, he told her of his nights in the Philippines and the girls he got there. Her mother slapped the American and was fired. This desire to move away from the periphery is repeated throughout the narrative, with scenes of her mother shrieking and jumping up and down with joy when Ms Philippines wins the Ms Universe contest: “America got the moon, but the Philippines won the Universe.” And they turn it around by parroting questions such as: “Is Manila still full of monkeys, hohoho.” This is a glocational trope that reveals the border position of a nation.

Nation, or the trope that reveals their sense of themselves, is a constantly shifting space for the two sisters. Through their mother, America is their nation. When they go back to the Philippines, they try to “make the change a temporary transliteration — as if (they) weren’t shifting from one discrete language to another but mainly living in different symbols, substituting rather than transforming. (They) jealously guarded the shadows of Wilmington — the language of English for one — or we tricked each other with tales, i.e., with true and untrue memories, so that one could correct the other.” When they receive the boxes filled with things from America, they finally recognize that their time in America is over: “Our worldly effects unthinkable in our native land: skate in the ocean, shiny jersey zippered look wading in the floods.”

Their frequent migrations take their toll on them, coming out as 24 A Locational Feminist Reading of Filipina-American Fiction:

border thoughts: “And there was too much for memory to account for: could so much be unmemorable? Could we have missed numerous other possibly memorable events merely by moving away, by not having items close by?” Vicky chooses to go back and live in Massachusetts. From foreigner to native to visitor in her home country, she is welcomed by “sighs, exclamations, shrieks, food of island proportions… I tried to take in all the abundant gestures and crammed objects in the apartment, grown smaller with each of the family’s regular migrations when we’d escape from rent and take with us only our belongings.”

These three women’s memories are both connected and disjointed. Vicky remembers the “tattoo of a sunflower with diminishing petals on the arm of a possible criminal.” This seems to be referring to the nextdoor neighbor Frank who heaved a stereo up above his head in rage: “It remains there above his head. Certain memories are locked like that.” Her memories of Frank are linked with her memories of her mother: “I remember I’d wake up at nights to a solid, fleshy moon and creep about to see where mother had slept — she ended up at various beds, like a night nurse, a hundred pound angel.” She associates the men surrounding her mother with rage and knives, as when her father comes home from Pookie’s parents. These frozen and unclear memories are very much a border experience for Vicky: “Now when I try to figure out the facts form the enigmas, the mysteries remain.”

This conjunctural trope is repeated throughout the narrative: “From dream-sleep to dream of present, I looked at dolls, dresses, my shirt in the dream, and smelled that smell — becoming weirdly sweet with familiarity — that came from packaged foreign objects, as if displacement had some perfume, emerging magically from the unravelling of things. And all I thought about, after this trauma of carnivorous moms, was this swing I once swung on in the grass of someone’s yard. My mnemonic treasures are odd, out of place, like flung glass beads from bitten strings.” The unreal world of dreams, plastic dolls, the real smell of foreign things, a memory, once more of swinging at a neighbor’s yard — all these combined make up Vicky’s memory of their past life in America. Paradoxically, she, the voice narrating this story, does not know everything that has happened, and cannot be sure if they ever happened. This is the uncertainty that often marks border identities which are rooted neither here nor there.

Her cheerful, older sister Stella, now residing in the Philippines, has a different memory of America: “I hated those lies, those stories about America — that it was the best thing that could have happened to us…The way Mommy spanked us when we didn’t speak English. I was so proud of the language that no one else in Wilmington knew.”

Unlike Vicky who has gone back to live in Massachusetts, Stella stayed in the Philippines with their mother. Until this conversation, Vicky had believed her mother’s perception of the American dream. She recalls that she was proud of her free lunch ticket, having been told by her Mom that it was a privilege, “being Filipino and all.” Yet Stella is clear about what she remembers: “The worst things are the stories. As if she’d never been discriminated against, even by those evil old neighbors she had to live with. I feel sorry for her and I’m angry.”

Towards the end of the narrative, the reader is again thrown offcourse about who really holds the true memories. Stella speaks about skating in the neighborhood park and Vicky says: “That’s my memory. I remember it being really cold and I’d still go out, and I remember the solitude: I remember those spaces of solitude in America.” To this, Stella replies: “Really? Then maybe it was yours — your memory that you’d traded with me before, and I’ve kept it.”

Within that border space between her mother and her older sister, Vicky is the teller of stories both real and unreal, the holder of incomplete memories. She looks at both of them: “The woman at the bank teller’s window, who had once been French, Vietnamese, Persian all at once, who had slugged the American vet, was nowhere in those murky features — whereas Stella was growing stouter and more vibrant a presence, like an overwhelming flood of memory.”

For both Stella and Vicky, it has become clear that their old American neighborhood was not the best place to live in. Their Mom however says: “I didn’t know that was what the neighborhood was. I thought it was just America.”

During my conversations with first generation Fil-Ams, I would playfully ask them: “If you were watching a game between teams from America and the Philippines, whom would you root for?” Sometimes I am met with silence. Sometimes, the answer is immediate: the Philippines. However, if you ask a teen-age Filipino-American who was born here, s/he would immediately say, “America, because I am American.” In other conversations, one Filipina-American plans to resign from her high-profile job to buy land in the Philippines and plant vegetables in a farm somewhere in the provinces, while a caretaker of elderly persons in Chicago works both night and morning shifts because she wants to save and “retire” in the Philippines.

The search for “home” is seen as the context for the international diaspora of Filipinos (Strobel 29). The trope of nation, evident in these stories through the women’s identification with their bodies (e.g., one teenage girl preoccupied with Barbie and another awaiting her period), memories (e.g., through pictures in the story Montes), and imaginations (e.g., Toni’s imagined conversation with the American), is fraught with notions of home, exile, and belonging — the “holy triumvirate” in the very idea of diaspora. The sense of belonging floats between nostalgia for the native land and the desire to possess (and be possessed) by the adopted one. Many characters in these stories recognize that the exercise of memory is the only means of keeping in touch with that part of their hybrid, hyphenated identity (Bose 163-168).

The narrative of “nation” is contained in the story of the self, and to locate one’s personal history within the history of the community is to find the relationship between the self, the nation, and the narration. This is the beginning of decolonization (Pierce 37). It is necessary to look at the daily performances of women and the ways by which they (re)write the nation on the margins — a nation that is dynamic and fluid, steeped with the complexity of their individual, daily participation, which is the creative force at the root of nation building (Westlake 19). The character is a repository for individual and collective memory. Sulit calls this a collapsing of the personal and political which allows for the emergence of a national and transnational literature, offering the ways in which nations construct one another ("Pinay Writings" 370).

“Border” spaces of longing, liminality, paradoxical processes of connection and separation and cultural hybridization are occupied by the characters in these stories, for instance, Maria Elizabeth playing Double Dutch, or “wild” Ina defying all conventions. Colonized and overdetermined from without, Filipinos are not just born “split,” but are also born on the “border.” Filipina-Americans are citizens of nowhere, neither entirely included in nor completely excluded from the American landscape, “wards” and “nationals” but not citizens of the United States (Sulit, "Philippine Diaspora" 124). Gayatri Spivak speaks of the diasporic woman as transnationally located, the site of global public culture privatized, spending her entire energy upon the successful transplantation or insertion into the new state, and possibly the victim of an exacerbated and violent patriarchy which operates in the name of the old nation as well (qtd in Bose 167).

In this “third space,” there is always the question of whether identity is to be true to its origins or to the adopted culture, or whether to embark on the more difficult path of constructing a self that acknowledges both (Bose 163). Amy Kilgard speaks of liminal experiences as moments of heightened awareness of the relationships between images, ideas, people, and things; and of border crossing as living on and with the edges (Kilgard 146). Born hybrid, one is constantly struggling to maintain a consistent and coherent identity between physical and metaphysical cultural borders: “You personify the colonizer at the same time that you are colonized; you participate in the colonization of yourself ” (Pierce 33). Filipina-Americans constantly live with the concept of borderland, its multiple boundaries, interconnectedness, fluidity, and creativity (Strobel 26).

“Migration to a new society necessitates and enables a new positioning of the self” (Erel 239). The “movements” experienced by the characters in these stories complicate their sense of belonging, exile, and nostalgia. For instance, for the two sisters and their mother moving back and forth between the Philippines and America in the story “Wilmington,” home is a transient location, whether imaginary or real (Bose 167).

These stories deconstruct the stereotypical fixation of migration as a unilinear journey (Erel 240). Like the characters in Meneses’ and Palarca’s stories, many Filipinos leave their home country for the “American dream,” to promises linked to the “value of whiteness”: economic opportunity, equal treatment under the law, and the promise of each individual’s right to pursue happiness. Pierce speaks of the history of the US as a long and repetitive narrative of the inaccessibility of the promises of the American dream to many people and communities of color (Pierce 36). 28 A Locational Feminist Reading of Filipina-American Fiction:

Filipino-Americans are the second fastest-growing Asian/Pacific Islander community in the US (constituting 18% of total Asian/Pacific Islander population), according to a 2000 US census. As shown in the stories, there is a continuing sense of marginalization, and dominant themes of lost identities and histories. Oft-written about is how the double heritage of dual colonizations (first, by Spain then by the US), coupled with American imperialism, has left an indelible mark on the FilipinoAmerican psyche. Epifanio San Juan Jr speaks of the predicament and crisis of dislocation, fragmentation, loss of traditions, exclusions and alienation of Filipino-Americans, while Oscar Campomanes refers to the crisis Filipino/American identity’s imperial nationality as one of “amnesia,” transcribed by powerful acts of forgetting and impressions of formlessness. Rightfully, Eric Gamalinda points to the Filipino’s “invisibility” as a consequence of amnesia, still regarding their own culture as inferior. “It is no wonder that second- and third-generation Filipino-Americans feel they are neither here nor there, perambulating between a culture that alienates them and a culture they know nothing about or are ashamed of ” (qtd in De Jesus 3).

The “glocational” trope, exemplified in the effect of the Barbie doll on Perla in the story by Bueno, shows how the local, the private, and the domestic are constituted in relation to global systems. This corresponds to the idea of the “local” mentioned by Susan Friedman in her discussion of geopolitical literacy or the “ordinary and everyday” in Toril Moi’s concluding statements in her book, Sexual/Textual Politics.

The process of decolonization allows for the recognition of identity as tied to global discourses and colonial imperialism. By virtue of being born, a Filipino inherits four hundred years of combined colonization. With the combined forces of colorism by Spain and racism by the US, the internalized notion of “White is beautiful” continues to inferiorize Filipinos. In Maria P. P. Root’s words: “You come to understand that your life, your family, your day-to-day interactions that were once so personal are actually part and parcel of particular social constructions of race, gender, class, and nation” (qtd in Pierce 33).

The glocational trope can also point to the greater community to which Filipina-Americans belong. Diaspora holds the notion of “interconnectedness.” The effects of colonization, internationalism, globalization, and the transplantation of Filipinas (Pinays) living in the United States affect those who live in the Philippines, Australia, and elsewhere, and vice versa (Tintiangco-Cubales 142-143).

Moving beyond the text, women writers of the Philippine diaspora embody a literature of witness, encompassing a kind of two-way vision of Filipino diasporic community, one that investigates the dialectic of homogenization and differentiation in a world system, the position of crisis for the writer constructing narratives of the diaspora, and the obstacles that Filipinos face in forming communities of empowerment to resistance. David Leiwei Lim articulates the struggle of a writer to choose between the obligation to their immediate communities and the demands of a consumer culture (qtd in Sulit, "Philippine Diaspora" 126127) Carolyn Pedwell suggests that authors may need to think further, not only about the kinds of subjects and voices that the cultural and political contexts they are concerned with engender, but also the kinds of subjects their own discourse (re)produces and ‘gives voice’ to (196). In the end, what matters is how writers modulate transnational, national, and personal voices alike (Simal and Marino 15-16).

The trope of conjuncturalism is inextricably tied to the border experience, and not just of the characters found in these stories. Conjuncturalism, as found in the texts of Bueno, Galang, Montes, and Apostol, among others, is about juxtapositions, intersections, and interconnections of different cultural formations written by the writer and read by the critic. There are intersections of cultural essentialism and racism, gendered and sexualized processes of domination, and distinct embodied practices and cultural groups (Pedwell 197). In Bueno’s and Galang’s stories, religion intersects with tradition, gossip is juxtaposed with history. In Montes and Apostol’s stories, memory is juxtaposed with history until one is not certain which is real or imaginary.

The concept of nation in all its local aspects, its links to the global village, along with notions of migrations across borders resulting in hybridization and transculturation is crucial in understanding the overdetermined positions, and therefore the multi-layered subjectivities and identities of the Filipina-American. This revelation becomes an interrogation of the normalized violence manifested by the erasure of the Philipine-American history and culture, as well as the silencing of Filipina-American voices. This interrogation paves the way towards breaking that silence and towards recovering that which has been erased.

Works Cited

Arvanitakis, James. “Colonialism and the Emergence of Hope.” Emergent Writing Methodologies in Feminist Studies. Edited by Mona Livholts. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Apostol, Gina. “Wilmington.” Catfish Arriving in Little Schools. Edited by Ricardo M. De Ungria. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing, 1996.

Bohan, Janis S. “Sex differences and/in the self: Classic themes, feminist variations, postmodern challenges.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 26, (2002).

Bose, Brinda. “Of Displaced Desires: Interrogating ‘New’ Sexualities and ‘New’ Spaces in Indian Diasporic Cinema.”New Femininities: Post feminism, Neoliberalism and Subjectivity. Edited by Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Brainard, Cecilia Manguerra et al., editors.Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults. Kindle Edition. Santa Monica, CA: PALH, 2015.

Budgeon, Shelley. “The Contradictions of Successful Femininity: Third Wave Feminism, Postfeminism and “New’ Femininities.” New Femininities: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism and Subjectivity.Edited by Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Cruz, Denise. Transpacific Femininities: The Making of the Modern Filipina. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2012. Dahl, Ulrika. “The Road to Writing.” Emergent Writing Methodologies in Feminist Studies. Edited by Mona Livholts. New York: Routledge, 2012.

De Jesus, Melinda. “Introduction: Toward a Peminist Theory, or Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience.” Pinay Power: Peminist Critical Theory: Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience. Edited by Melinda de Jesus. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2005.

Erel, Umut. “Migrant Women Challenging Stereotypical Views on Femininities and Family.” New Femininities: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism and Subjectivity.Edited by Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff.New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Friedman, Susan Stanford. “Locational Feminism: Gender, Cultural Geographies, and Geopolitical Literacy.” Feminist Locations: Global and Local, Theory and Practice.Edited by Marianne Dekoven.U.S.A: Rutgers University Press, 2001.

Galang Evelina M. “Her Wild American Self.” Her Wild American Self. Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 1996.

Kilgard, Amy K. “Directing Performances of Border Crossing: An Allegory of Turnst(y)les.” Casting Gender: Women and Performance in Intercultural Contexts. Critical Intercultural Communication Studies. Thomas K. Nakayama, General Editor, vol 7. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2005.

Moi, Toril. Sexual/Textual Politics: Feminist Literary Theory.2nd ed. New York: Routledge, 2002. Montes, Veronica. “Apollo & Junior Grow Up.” Going Home to A Landscape: Writings by Filipinas.Edited by Marianne Villanueva and Virgina Cerenio. Minneapolis: Calyx Books, 2003.

Palarca, Julia. “Restaurants Are Crowded in America.” Fiction by Filipinos in America. Edited by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, 2015, ebook, PALH. 16 November 2016.

Pedwell, Carolyn. “The Limits of Cross-Cultural Analogy: Muslim Veiling and ‘Western’ Fashion and Beauty Practices.” New Femininities: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism and Subjectivity.Edited by Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff.New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Pierce, Linda M. “Not Just My Closet: Exposing Familial, Cultural, and Imperial Skeletons.” Pinay Power: Peminist Critical Theory: Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience. Edited by Melinda de Jesus. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2005.

Simal, Begoña and Marino Elisabetta, editor. “Introduction: Approaching Different Literary Voices in Asian America and the Asian Diaspora.” Contributions to Asian American Literary Studies: Transnational, national and Personal Voices: New Perspectives on Asian American and Asian Diasporic Women Writers. Vol. 3. New Jersey: Rutgers University, 2004.

Strobel, Leny Mendoza. “A Personal Story: On Becoming a Split Filipina Subject.” Pinay Power: Peminist Critical Theory: Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience. Edited by Melinda de Jesus. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2005.

Sulit, Marie-Therese C.“Through our Pinay Writings: Narrating Trauma, Embodying Recovery.”Pinay Power: Peminist Critical Theory: Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience. Edited by Melinda de Jesus. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2005. ---. “The Philippine Diaspora, Hunger and Re-Imagining Community: An Overview of Works by Filipina and Filipina American Writers,” Contributions to Asian American Literary Studies: Transnational, National and Personal Voices: New Perspectives on Asian American and Asian Diasporic Women Writers.Edited by Begoña Simal and Marino Elisabetta, vol. 3. New Jersey: Rutgers University, 2004.

Tintiangco-Cubales,Allyson Goce. “Pinayism,” Pinay Power: Peminist Critical Theory: Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience. Edited by Melinda de Jesus. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2005.

Tong, Rosemarie. Feminist Thought (3rd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 2009. Westlake, E.J. “Theoretical Foundations and Intercultural Performance: (Re) writing Nations on the Margins.” Casting Gender: Women and Performance in Intercultural Contexts. Critical Intercultural Communication Studies.Thomas K. Nakayama, General Editor, vol 7. New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc., 2005.

Erratum:

In Vol 39, p 33, De Vega should be "Vega"

in “The De Vega’s Wartime Episode”

by Christian G Mundo.

No comments:

Post a Comment