Review of Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults, by Karen Pierce Gonzales, Folkheart Press website, Dec. 29, 2009

What I like most about folk stories is that they tell us something important about other people. They create specific examples of universal themes that exist in all cultures; they express the uniqueness of a particular time and a particular people that enlightens us all about our own humanity.

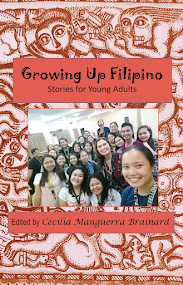

This is what I recently experienced after reading Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults, a collection of contemporary stories for young adults collected and edited by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard. The 257-page book published by PALH (Philippine American Literary House) was first brought to my attention by fellow writer Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor. A bright writer herself who lives in Washington, she was able to share with me not only the beauty of her own literary work but also the richness of her cultural heritage.

Thanks to her I was allowed into the post 9/11 world of Filipino and Filipino American youth. Through this I was introduced to a culture that admittedly I knew very little about.

I learned through the stories that many Filipino children are raised in a very strong patriarchal system that often over rules the individual child’s needs to ‘fit in’ with the dominant American culture. For example, in ‘Double Dutch’ (Leslieann Hobayan) when young Maria Elizabeth comes home one day with her hair braided by her African American school friend her family responds by telling her the braids are ugly and she is no longer allowed to play with her friend. I could feel the poignancy of Maria Elizabeth’s dilemma as she withdrew from the schoolyard community she enjoyed so much.

Other stories also reveal the hard facts of immigrant life. Alma (‘Here in the States’ by Rashaan Alexis Meneses) struggles to understand how hard her mother must work as a nanny to make ends meet. Shame and sadness mingle when she questions the discrepancy between her mother’s role as a respected professional back home and her new role as a domestic helper. Adolescent resentment and rebellion about having to help care for younger siblings (something the maid back home did) further complicate Alma’s efforts to make sense of this new world. It is in her mother’s quiet strength and acceptance of life’s uncertainties that Alma finds her greatest comfort and connection.

While the book is designed to reflect the issues young adults face, it does much more than that. It reaches out to the rest of us in a way that invites deeper understanding and awareness of how our Filipino and Filipino American brothers and sisters experience life in America. Fraught with the angst of adolescence that exists everywhere and grounded in an abiding sense of strong Filipino family/cultural values, the authors of these stories have something valuable to tell us about our own desires and struggles to belong in whatever world we live in.

We are fortunate to have access to such a formidable anthology. It is certainly a must read for anyone who wants to celebrate our multicultural society.

Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults will be released March, 2010. For more information, visit their website.

Posted by Karen Pierce Gonzalez at 9:19 AM

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

REVIEW OF GROWING UP FILIPINO II, by Karen Pierce Gonzalez, Folkheart Press

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Monday, December 28, 2009

Book Launch of Growing Up Filipino II, Jan. 16, 2-5 p.m. San Francisco

Edwin Lozada and Veronica Montes have been working together on the following book launch of Growing Up Filipino II, cosponsored by PAWA (Philippine American Writers and Artists) and Arkipelago Books, on Sat. Jan. 16, 2010, 2-5 p.m. at the Bayanihan Community Center, 1010 Mission St., San Francisco. Contact pawa@pawainc.com for more information.

I am sure there will be a Literary Reading by contributors in the Bay Area. I will update this post as I get more information. (Thanks Edwin and Veronica!)

I am sure there will be a Literary Reading by contributors in the Bay Area. I will update this post as I get more information. (Thanks Edwin and Veronica!)

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Growing Up Filipino II, by Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor

Thoughts on the new book Growing Up Filipino II, by Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor

I love books. The weight. The smell. The deliberate slowness of reading and turning a page and reading some more.

The screen just isn't the same and that's good and bad. Good for scanning and absorbing information quickly. Bad for reflection and immersion.

I get lost in the process of reading books, lost in new worlds and new people.

Escapism doesn't begin to cover the sensation of unfolding a completely different universe with the flick of the wrist as each page turns.

My author copies of Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults arrived a couple of weeks ago.

In the run-up to Christmas, I had just enough time to show it off to a few friends and family, but very little time to really absorb what I held in my hands.

My first in-book publication.

Don't misunderstand - I'm grateful to the print and online magazines that have published my poetry and reviews. Each byline meant that I became less a could-be writer and more a in-fact writer.

But to hold my story in my hands, all printed and bound up with fabulous work by authors I admire as really-real writers, I stepped into a whole new world I knew existed, but didn't think I had the key to open.

With a flick of my wrist, I was there, in the book, a story peering back at me the reader, a reader peering into a writer's world and that writer was me.

And by 'was' I mean a past me, the one who wrote the snippet of the story over 5 years ago, polished it and submitted it 2 years ago, received an acceptance and proofed my galley last year, and proofed it again this year.

I'd been told that the birthing of a story takes a long time, and I thought that only meant the creation of it. I understand now that there's also the production of it, the long steps from one universe to the next. Who knew that the the distance from the front of the wardrobe to the back was so long, Lucy?

So, there's writing, then there's book-making, and now comes the book promoting.

The hardcover version is now available at Amazon and the soft and hardcopy versions can be ordered from your local brick and mortar store. Just tell them that they can get them from Ingram or Baker & Taylor.

If you know any of the contributors (Dean Francis Alfar, Katrina Ramos Atienza, Maria Victoria Beltran, M.G. Bertulfo, Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, Amalia B. Bueno, Max Gutierrez, Leslieann Hobayan, Jaime An Lim, Paulino Lim Jr., Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor, Dolores de Manuel, Rashaan Alexis Meneses, Veronica Montes, Charlson Ong, Marily Ysip Orosa, Kannika Claudine D. Peña, Oscar Peñaranda, Edgar Poma, Tony Robles, Brian Ascalon Roley, Jonathan Jimena Siason, Aileen Suzara, Geronimo G. Tagatac, Marianne Villanueva) ask your bookstore owner if they'll set up a reading to promo the book, then let your friends, family, and total strangers you meet at the coffee shop or grocery store know.

Step into the stories imagined in a post-9/11 world, written from the perspective of the young adult but accessible to anyone who has struggled with issues of family, love, sexuality, home, and social change in the current modern age.

Tuloy! Come share our world.

Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor's blog is http://wordbinder.blogspot.com/

I love books. The weight. The smell. The deliberate slowness of reading and turning a page and reading some more.

The screen just isn't the same and that's good and bad. Good for scanning and absorbing information quickly. Bad for reflection and immersion.

I get lost in the process of reading books, lost in new worlds and new people.

Escapism doesn't begin to cover the sensation of unfolding a completely different universe with the flick of the wrist as each page turns.

My author copies of Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults arrived a couple of weeks ago.

In the run-up to Christmas, I had just enough time to show it off to a few friends and family, but very little time to really absorb what I held in my hands.

My first in-book publication.

Don't misunderstand - I'm grateful to the print and online magazines that have published my poetry and reviews. Each byline meant that I became less a could-be writer and more a in-fact writer.

But to hold my story in my hands, all printed and bound up with fabulous work by authors I admire as really-real writers, I stepped into a whole new world I knew existed, but didn't think I had the key to open.

With a flick of my wrist, I was there, in the book, a story peering back at me the reader, a reader peering into a writer's world and that writer was me.

And by 'was' I mean a past me, the one who wrote the snippet of the story over 5 years ago, polished it and submitted it 2 years ago, received an acceptance and proofed my galley last year, and proofed it again this year.

I'd been told that the birthing of a story takes a long time, and I thought that only meant the creation of it. I understand now that there's also the production of it, the long steps from one universe to the next. Who knew that the the distance from the front of the wardrobe to the back was so long, Lucy?

So, there's writing, then there's book-making, and now comes the book promoting.

The hardcover version is now available at Amazon and the soft and hardcopy versions can be ordered from your local brick and mortar store. Just tell them that they can get them from Ingram or Baker & Taylor.

If you know any of the contributors (Dean Francis Alfar, Katrina Ramos Atienza, Maria Victoria Beltran, M.G. Bertulfo, Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, Amalia B. Bueno, Max Gutierrez, Leslieann Hobayan, Jaime An Lim, Paulino Lim Jr., Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor, Dolores de Manuel, Rashaan Alexis Meneses, Veronica Montes, Charlson Ong, Marily Ysip Orosa, Kannika Claudine D. Peña, Oscar Peñaranda, Edgar Poma, Tony Robles, Brian Ascalon Roley, Jonathan Jimena Siason, Aileen Suzara, Geronimo G. Tagatac, Marianne Villanueva) ask your bookstore owner if they'll set up a reading to promo the book, then let your friends, family, and total strangers you meet at the coffee shop or grocery store know.

Step into the stories imagined in a post-9/11 world, written from the perspective of the young adult but accessible to anyone who has struggled with issues of family, love, sexuality, home, and social change in the current modern age.

Tuloy! Come share our world.

Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor's blog is http://wordbinder.blogspot.com/

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Friday, December 25, 2009

Christmas Carolling at the Brainards

Labels:

Cecilia Brainard,

Christmas carolling,

family,

friends

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Thursday, December 17, 2009

IN MEMORIAM KIRKUS REVIEWS

Kirkus Reviews will close at the end of the year. From LA Times, "Kirkus was founded in 1933 and was published biweekly. It relied on a small staff and an army of freelancers who reviewed about 5,000 books a year three months before their publication dates. Authors looked to Kirkus reviews to test how their books would be received; libraries and independent bookstores turned to them to decide what to buy."

I didn't realize until now how well-respected the book reviews by Kirkus have been, since Kirkus did not hesitate giving bad reviews, "When I was a book publicist, the worst part of my job was having to read a Kirkus review over the phone to an author. 2 cigs before, 2 after,” recalled Laura Zigman, an author and former book publicist for Alfred A. Knopf, in a Twitter post.

To express my sadness at the closing of Kirkus, I post here a review of When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, published in Kirkus Reviews, July 1, 1994.

When the Rainbow Goddess Wept by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard (first published by Dutton, current publisher is University of Michigan Press)

"A fast-paced,sensitively written first novel about the psychological damage war wreaks, seen through the eyes of an intelligent resilient young girl.

During WWII, as Japanese forces invade her native city of Ubec in the Philippines, nine-year-old Yvonne Macaraig escapes with her father and mother into the mountains, where they stay in villages whose inhabitants are fighting the Japanese. Yvonne's father, an engineer, joins a guerrilla regiment. In wartime, Yvonne learns, people change. Her mother bears a stillborn baby in the jungle while Japanese soldiers lurk nearby, prevents an enemy soldier from stealing their chickens, and asks Yvonne's father to kill the prisoner of war he takes. Her father refuses, but confesses after he shoots the man for trying to escape that he enjoyed killing him, as revenge for the dead baby. When Yvonne's father disappears on a mission, the girl develops the "practicality" war requires. "I wondered what we would do if Papa were really dead. Would the guerrilleros cast us aside...?" She refuses to give up hope and "learns how to will (her) father to live...centering (her) energy on keeping Papa alive." The author, herself born in the Philippines, skillfully interweaves realistic events with myths of women fighters and goddesses, as well as fantastic dreams. She relates dramatic events in an understated way, such as the family's ride up into the mountains on horseback, with a spare horse carrying dynamite, and she enhances her understanding of Yvonne's pre-war world through the use of ironic details: In the Ubec cinema "the roof leaked...From the loge, one could see the movie reflected upside down on the wet floor."

Brainard's appealing characters are larger-than-life people who change before our eyes, yet remain convincing." -

Thank's again Kirkus for this review and I'm sorry you won't be around! Kirkus must have judged the novel correctly because When the Rainbow Goddess is still in print 15 years later.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Saturday, December 12, 2009

Merry Christmas from the Brainards

Labels:

Holiday greetings,

Merry Christmas

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Sunday, December 6, 2009

The Christmas Tree is Up!

The Christmas Tree is Up!

Some favorite Christmas tree decorations: the black sheep, the ballet dancer, the antique German-made glass bird, and the bird in the nest.

Some favorite Christmas tree decorations: the black sheep, the ballet dancer, the antique German-made glass bird, and the bird in the nest.

Labels:

christmas,

decoration,

holiday,

tree

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Thursday, December 3, 2009

Pictures Machu Picchu and Pablo Neruda's House

I'm sharing pictures taken in Macchu Picchu and in Pablo Neruda's House in Santiago, Chile (Las Chascona). They're a few years old, but I remembered them.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Monday, November 30, 2009

LISTED IN AMAZON.COM GROWING UP FILIPINO II: More Stories for Young Adults

Amazon.com now lists the hardcover of Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults, click on this site:

<http://www.amazon.com/Growing-Up-Filipino-II-Stories/dp/0971945829/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1259619206&sr=1-2>

~~~~

DISTRIBUTED BY: Ingram, Baker & Taylor, Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, among others

PUBLISHED BY:

PALH

P. O. Box 5099

S.M., CA 90409

Tel/fax: 310-452-1195; email:palh@aol.com; palhbooks@gmail.com;http://www.palhbooks.com

BOOK DESCRIPTION: Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults is the second volume of the Growing Up Filipino series by PALH. In this collection of 27 short stories, Filipino and Filipino American writers explore the universal challenges and experiences of Filipino teens after the historic events of 9/11. The modern demands do not hinder Filipino youth from dealing with the universal concerns of growing up: family, friends, love, home, budding sexuality, leaving home. The delightful stories are written by well known as well as emerging writers. While the target audience of this fine anthology is young adults, the stories can be enjoyed by adult readers as well. There is a scarcity of Filipino American literature and this book is a welcome addition.

CONTRIBUTORS: Dean Francis Alfar, Katrina Ramos Atienza, Maria Victoria Beltran, M.G. Bertulfo, Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, Amalia B. Bueno, Max Gutierrez, Leslieann Hobayan, Jaime An Lim, Paulino Lim Jr., Rebecca Mabanglo-Mayor, Dolores de Manuel, Rashaan Alexis Meneses, Veronica Montes, Charlson Ong, Marily Ysip Orosa, Kannika Claudine D. Peña, Oscar Peñaranda, Edgar Poma, Tony Robles, Brian Ascalon Roley, Jonathan Jimena Siason, Aileen Suzara, Geronimo G. Tagatac, Marianne Villanueva

BIO OF EDITOR: Cecilia Manguerra Brainard is the award-winning author and editor of over a dozen books, including the internationally-acclaimed novel, When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, Magdalena and Acapulco at Sunset and Other Stories. She edited Growing Up Filipino: Stories for Young Adults, Fiction by Filipinos in America, and Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and co-edited four other books. Cecilia also wrote Fundamentals of Creative Writing (2009) for classroom use. She teaches at UCLA-Extension’s Writers Program.

Labels:

filipino american literature,

literary anthology,

literature,

Philippine American literature,

short stories,

young adult

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Friday, November 27, 2009

Book Review - Finding God: True Stories of Spriritual Encounters

Book review of "Finding God" BY ALLEN GABORRO (Philippine News, November 20, 2009)

TITLE: Finding God: True Stories of Spiritual Encounters

Edited by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard and Marily Ysip Orosa

PUBLISHER: Anvil Publishing (Manila)

158 pages

nonfiction

Distributed in the US by palhbooks.com, email palhbooks@gmail.com

http://www.palhbooks.com/cbrainardfg.html

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“Finding God: True Stories of Spiritual Encounters” is a righteous anthology of works that focus on the mark that God has made on the book‘s writers. A total of 18 pieces have been contributed to “Finding God” which was put together and edited by author Cecilia Manguerra Brainard and book publisher Marily Ysip Orosa.

Their publication is timely, depending of course on how you would identify yourself as either a religious person, an agnostic, or as a non-believer. The book attempts to fill the void between Christian ideals and the confounding reality of our modern, secular existence by trying to inspire its reading audience into realizing a closer, more personal relationship with God. And in a time when Filipinos and Filipino Americans are ever-mindful of the pressing demands of the temporal world, “Finding God” seeks to rebrand humanity with God’s fullness and grace.

At the risk of sounding evangelistic, Brainard and Orosa have touted their anthology as nothing less than “God’s book” and that they were “His tools” in the creation of that book. A little melodramatic perhaps, but that is not to say that the true believing reader will not feel God’s presence throughout the pages of “Finding God.” In fact, it is not an exaggeration to say that the editors have indisputably attributed the conception and the production of the book to God himself.

“Finding God” finds unity in diversity as it respects the authors’ individualism and the awareness that they share something in common that is very sublime and transcendent. That something is their Christian faith and it is the glue that holds all of the book’s contributors together. Brainard and Orosa apply that faith to create a consensus of spirituality out of a collection of people who, judging from the multiplicity of their backgrounds, may not agree at all on other issues.

Foremost among the stories in “Finding God” is the anthology’s very first one, titled “Losing God” by Mila D. Aguilar. To understand Aguilar’s essay, one need look no further than her life both as a young girl and then later, as a political revolutionary. As a young girl, Aguilar determined that God did not exist, that “there was no God, that he was but a figment of man’s imagination.” Her first-hand look at poverty in the Philippines caused Aguilar to conflate the deprivation she saw with the nonexistence of God. Consequently, her mindset acknowledged no other philosophy other than atheism and communism “as the ultimate solution to social inequality.”

The images of Aguilar’s arrest and incarceration in 1984 by Ferdinand Marcos’s security forces are filled with tension, drama, and danger. Surviving her imprisonment becomes tenuous at one point, as one of her interrogators implies that her days on earth are numbered. Ironically it is at this point that Aguilar, the atheistic revolutionary, refers her fate to a divinity in her moment of impending doom: “If that is what God wills…I was as ready to die or be butchered.” Aguilar eventually finds her way to God after her release from prison following the downfall of the Marcos regime.

A spiritual being can easily find divine inspiration in the collection’s narratives for “Finding God” reverently depicts the vital spirituality that colors its assortment of stories. However, a principally secular humanist and rationalist—there are far more of them among Filipinos and Filipino Americans than one might think—would take issue with this. The book is to the Filipino Christian faithful what a prayer meeting is to a gathering of devoted attendees. “Finding God” conveys a message that is totally commensurate with the Christian worldview and ethos, but one that is also at variance with any model of critical discussion. In this sense, Brainard’s and Orosa’s publication is a microcosm of Christianity’s immutable version of compassionate conservatism and pathos.

With seemingly intricate candor, “Finding God” tries to do justice to the completeness of God by posing an interchange between the spiritual lives and faith of its contributors and those who choose to closely consider the moral and historical contradictions that surround the Christian religion. By doing so, the book’s editors deliver a spiritually sobering yet uplifting message of faith that some readers will embrace and others will take with a grain of salt.

ALLEN GABORRO

Labels:

book review Finding God

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Thursday, November 26, 2009

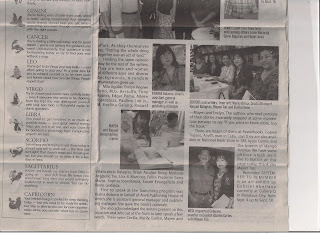

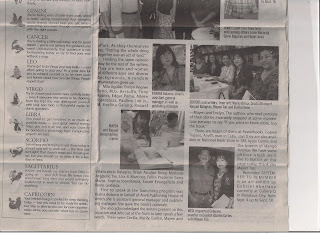

News Coverage of Finding God Book Launchings

My friend Chinggay Utzurrum send some news articles about the book launchings of the book Finding God: True Stories of Spiritual Experiences, which Marily Orosa and I coedited (click on the image to get a bigger view). The pictures show: Karina Bolasco, Mayen Tan, Isagani Cruz, Marily Orosa, Evelyn Seno, Raquel Balagtas, Mila Aguilar, Evelyn Ramirez, Maribel Paraz, Brenda Arroyo,Mila Santillan, Joy Uytioco, Nina Yuson, Edna del Rosario,Carlos Cortes, Louie Nacorda, Gavin Bagares, Bobit Avila, Honey Loop, Carlos Cortes, and more :

Labels:

Finding God,

Philippines,

publicity

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

The Serenity Prayer

The Serenity Prayer

God grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

Living one day at a time;

Enjoying one moment at a time;

Accepting hardships as the pathway to peace;

Taking, as He did, this sinful world

as it is, not as I would have it;

Trusting that He will make all things right

if I surrender to His Will;

That I may be reasonably happy in this life

and supremely happy with Him

Forever in the next.

Amen.

--Reinhold Niebuhr

Labels:

meditation,

religious,

Serenity Prayer

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Sunday, November 22, 2009

The Freeman Article "Writers Pay Homage to the Queen City"

I have an essay in this anthology. I'm sorry I can't attend the book launching scheduled Nov. 27 in Cebu.

Cebu Lifestyle

Writers pay homage to the Queen City

(The Freeman) Updated November 21, 2009 12:00 AM

CEBU, Philippines - Anvil Publishing releases the third in a collection of books on cities with Cebu We Know, which will be launched on November 27, 4pm in Powerbooks Cebu at the SM Cebu North Wing. The book features essays by well-known Cebuano writers compiled by fictionist and columnist Erma Cuizon.

Located at the ‘very navel’ of the Philippine archipelago, Cebu is a center of trade and culture whose history is older than most cities in the country. As a layover to many people from Visayas and Mindanao, the island draws tourists and migrants who eventually call it home. Cebu is shown in its many facets and moods by the book’s contributors like Resil Mojares, Simeon Dumdum Jr. and Renato Madrid who write about its history and legends. Its coastline and beaches are the subject of essays by Erlinda Alburo, Charmaine Carreon and Hope Yu. Cebu is written of fondly by those who have left like Charmaine Fajardo and Cecilia Brainard.

Non- Cebuano writers also pay homage to this friendly city. In his foreword, Isagani Cruz writes, “From this book, I learned that writers can be inspired by almost anything on the island, such as horses, songs, cab drivers, stinginess, trees, seafood, corals, weeds, roast pig, coffee and schools. From what they experienced in Cebu, the writers in this book have weaved words of wonder, turning reality into literature”.

Labels:

anthology,

Cebu City,

Filipino literature

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Re When the Rainbow Goddess Wept

I got this email this morning; it makes my day.

Dear Ms. Brainard:

I am a student in Ms. Eve Caram's English 28 class, at LACC. I have had the pleasure of reading your novel, When The Rainbow Goddess Wept, and being an avid reader, I would like to let you know how much I truly enjoyed your book. I am looking forward to reading more of your books, as I am taking English 101 in the Spring. Ms. Caram speaks highly of you, and I am honored to be in her class. Thank you for your time and God bless you and your family. Happy Holidays!!

Respectfully,

A real fan,

________________ (I've deleted the person's name for her privacy)

Dear Ms. Brainard:

I am a student in Ms. Eve Caram's English 28 class, at LACC. I have had the pleasure of reading your novel, When The Rainbow Goddess Wept, and being an avid reader, I would like to let you know how much I truly enjoyed your book. I am looking forward to reading more of your books, as I am taking English 101 in the Spring. Ms. Caram speaks highly of you, and I am honored to be in her class. Thank you for your time and God bless you and your family. Happy Holidays!!

Respectfully,

A real fan,

________________ (I've deleted the person's name for her privacy)

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Saturday, November 21, 2009

WHERE THE DAYDREAMING CAME FROM, by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard

Click on Reprint with many pictures

(I'm sharing this personal essay to my readers. Copyright 2009 by Cecilia Brainard)

WHERE THE DAYDREAMING CAME FROM

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard

(part of the anthology Cebu We Know (Anvil 2009, Ed. Cuizon)

I have always been prone to daydreaming, traits which sometimes got me into trouble. “Pay attention, Cecilia!” the nuns used to tell me. The upside to the daydreaming is that the active fantasy world led to storytelling, which led me into writing.

But let me trace my beginnings to see where this daydreaming came from.

I was born and raised in the island of Cebu where my mother’s people came from. My father and his people came from another part of the Philippines – the North, Laguna specifically, where people spoke another dialect and ate meat and vegetable dishes with strong flavors. Laguna used to fascinate me for the simple fact that my father was born and raised there. Otherwise, it looked like any other provincial town, with a city hall, old church, and Spanish colonial stone and wood houses. I never lived there and only heard secondhand stories about my father’s family, about how, for instance, they had owned huge tracks of land which my grandfather gambled away. Laguna was a kind of mythic place which I didn’t really know.

It is Cebu I know. The very first breath I took was in Cebu. My first words were those spoken by Cebuanos. Even though I’d gone on to live in other places in the world, it is as if I carry a part of it within me always and likewise I feel as if Cebu has a place for me always.

My mother was in the nearby island of Opon for the fiesta of the Birhen sa Regla (Virgin of the Rule), patroness of the place, when her birth pains came. This was in 1947, two and a half years after Liberation. She had to catch the ferry to hurry to St. Anthony’s Maternity Clinic in Cebu City. It was Doctora Ramona Fernandez who assisted her. She had to be summoned when the waves of pain came in the early morning. On November 21, at 8:30 a.m. I was born, the fifth child of my mother, although one had died during wartime and so I grew up with three siblings. I was a large baby, almost 10 lbs, but with beriberi, a disease caused by thiamine deficiency and characterized by edema, weakness, irritability, and more serious problems such as heart problems. My mother suffered from lingering effects of World War II when she carried me in her womb. She was malnourished, which meant I too was malnourished. The lack of Vitamin B1 caused the beri-beri and I almost died.

My mother turned to the Santo Niño de Cebu, the Child Jesus patron of Cebu, famous for being miraculous. She danced her prayers just like the women you can still see shuffling their prayer-dances in front of the old stone church that houses the beloved Child Jesus. For the rest of her life, my mother always reminded me of my debt to the Santo Niño. “You owe your life to him,” she said, as she dragged us to hear Mass in the Santo Niño church. There I watched women dance their prayers and walk on their knees down the center aisle, and I smelled incense and burning candles, and looked in awe at the small-sized Niño clothed in red robes, while waiting for the interminable Mass to end. I continue to make it a point to visit the Santo Niño when I’m in Cebu.

Back in 1947 - from the clinic, I was brought to the house my family lived in, in Talisay. It was a temporary dwelling, a place my parents and their three children stayed in after the war ended. When they first got married, my parents lived in Manila but when World War II broke out, they evacuated to Mindanao, traveling by outrigger boats, with their two young children and some servants. My father joined the guerrilla movement in Mindanao, and there they had to move and hide from the Japanese soldiers. It was there where my mother gave birth to her third child behind some bushes with a Japanese patrol walking nearby; it was there where she lost her fourth child, a boy, whom we never discussed but who had taught my mother about the fragility of babies and life in general. The beri-beri had frightened her and when I was a girl she made sure I got my Vi-Dalin vitamins daily, and I had to drink milk every morning with breakfast. In the evening she made me take one raw egg – the whole slimy thing. She was constantly prodding me to eat, giving me choice morsels from the dining table, chicken gizzard and liver for instance. I recall a supper episode when I had to eat some dreaded vegetables, and finally to silence my mother I pretended to chew the veggies, only to secretly spit them into my hands and give them to one of our Police dogs.

That first house in Talisay belonged to my mother’s brother. The house was made of wood, on stilts, like a big nipa hut. It was situated near the sea and so early on I slept and awoke to the sound of waves lapping the shore and to fishermen shouting as they beached their outriggers. I was used to taking in the sea breeze and to having salt on my skin and in my hair. I was carried through coconut groves to the sandy beaches where I wondered at all the living things scampering on the gray sand, and where barefoot women sold fried bananas skewered together, and dripping with caramelized sugar. I ate rice, fish, pork, chicken, seaweed, mallungay, sweets made from coconut and sugarcane, and other simple straightforward foods still eaten by Cebuanos. Even now I will hanker for inununan, fish cooked in vinegar with crushed garlic, salt, and pepper.

My father worked as a District Engineer. He had done other things before the war but I’d only heard bits and pieces that he’d been to Thailand, that he’d worked for some bureau, and that he’d even worked in Indiana where he’d gone to engineering school. By the time I was born, he has 59 and had already led a full life. But I think that the more memorable things that my father did was teaching at the engineering department of the University of the Philippines, fighting as a guerrillero during World War II, and constructing roads and buildings, many of them still existing. I do not think I picked up my daydreaming from him because he was a very logical, methodical person.

I am not sure I got it from my mother either, who had a keen business mind, although she was more helter-skelter than my father. My mother said she was malnourished when she was carrying me within her because she would sometimes forget to eat. She and her lifelong friend, Mercedes Rodriguez, had a buy-and-sell business, and they sold things like army surplus goods and fire wood, and just about anything they could get their hands on. Later on, they went on occasional trips to Hong Kong to shop for merchandise to sell. All her life, my mother was busy with her business ventures. I’m sure that in Talisay, we children were left in the care of servants. My sisters talk of how my mother’s sisters looked down on us children because we smelled of fish or were not dressed nicely. This was possible since my mother came from a political family with some pretensions, and the kind of down-home style of living we had in Talisay was probably too “country” for my aunts who carried some ancient sibling rivalry with my mother. My mother’s sisters also questioned why my siblings attended the local public school instead of a private convent school. And why were we living in a glorified nipa hut as if it were still wartime and we were in the hinterlands of Mindanao?

It was probably my father, with his logical, methodical mind who decided we had to move to better quarters sooner or later. The event that may have precipitated our departure from the place was the horrific typhoon that blew into Cebu. The heavy rains caused waist-high floods and the violent sea rose and roiled up the local cemetery so that corpses floated about on the flooded streets. There were stories, which I can picture in my head as if they were my own experiences, of my siblings swimming through flooded streets to get home from school. Shortly after this, my parents finally talked about building their home in the city.

My mother’s brother helped my parents acquire the land in Cebu City, where they finally built our home, across some corn fields, near a river and the foothills, an area that was sparsely populated and remote. My father drew the plans and hired workers to construct the house. It was a Spanish-style house, with balconies, marble floors and crystal chandeliers. The surrounding grounds were spacious and my mother did most of the landscaping – fruit trees mostly – jack fruit, star apple, guava - flowering shrubs and low flowering plants. There was a teeter-totter and canopied swings so that even grownups could sit on the swings in the late afternoon to enjoy the cool breeze and supervise the gardener as he swept dry leaves and branches and burned them. We believed the smoke drove away mosquitoes and other insects. There was the main house with the kitchen, living room, dining room, bedrooms, bathrooms, veranda and balconies. There was another structure for the servants and for the cooking on the open hearth. There was a water tank and way in the back of the property was a garage, storage building, a place that I rarely visited because rats and monitor lizards lived in there, and more importantly, the nearby jack fruit tree had an agta, an enchanted black giant living in it. Needless to say there were endless stories about the agta, how the servants, even my brother had seen him one night when the moon was full. There were some other creepy happenings in our house: a maid became possessed and had to be exorcised by the Redemptorist priests; on Lent strange happenings would occur and all credited to the encantados that lurked around the area.

Indeed living in that house stimulated my daydreaming abilities because there were endless supernatural stories, as well as down-to-earth stories like love affairs and out-of-wedlock pregnancies. The radio soap operas in the early evening were also good primers in make-believe, because most evenings the servants listened to the convoluted plots dealing with love, revenge, and other deep human passions, all interlaced with conflict. I would sit and listen with them, in the outside kitchen with the open hearth, where I watched live chickens being decapitated for that night’s supper.

After a few years, the trees my mother had planted grew tall. I loved to climb the tall star apple trees with slender branches. There I indulged in fantasies about enchanted forests and magical giant pearls found in the heart of a banana fruit – the mutya. Sometimes I would get utterly lost in my dream world and would miss the call for lunch. Grumbling, my sister would have to threaten me in order for me to come down from those beloved trees.

When I was four my mother enrolled me in St. Theresa’s College. This ended the unhindered daydreaming I had in that house. My life became more regimented: up at 6 a.m., shower, don on the starched blue-and-white uniform, eat breakfast, leave for school by 7:15; first class at 8 a.m. I learned about rules and homework and sitting still with my hands folded together. This was the time I started to get scolded for daydreaming, that is for “not paying attention.” However the nuns did allow daydreaming when it came to theatrical plays and theme writing, which I loved. But I would say this was the time when I learned about discipline more than daydreaming.

###

Labels:

Cebuano,

personal essay,

Philippine American literature.Cecilia Brainard,

Philippine literature

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

PINOY (FILIPINO) SIGNS

Labels:

Filipino Philippines,

Pinoy,

signs

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Cecilia Manguerra Brainard's official website is ceciliabrainarddotcom. She is the award-winning author and editor of 22 books, including When the Rainbow Goddess Wept, The Newspaper Widow, Magdalena, Selected Stories, Vigan and Other Stories, and more. She edited Growing Up Filipino 1, 2, & 3, Fiction by Filipinos in America, Contemporary Fiction by Filipinos in America, and other books..

Her work has been translated into Finnish and Turkish; and many of her stories and articles have been widely anthologized.

Cecilia has received many awards, including a California Arts Council Fellowship in Fiction, a Brody Arts Fund Award, a Special Recognition Award for her work dealing with Asian American youths, as well as a Certificate of Recognition from the California State Senate, 21st District, and the Outstanding Individual Award from her birth city, Cebu, Philippines.

She has lectured and performed at UCLA, USC, University of Connecticut, University of the Philippines, PEN, Shakespeare & Company in Paris, and many others. She has served in the Board of literary arts groups such as PEN, PAWWA (Pacific Asian American Writers West), among others.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)