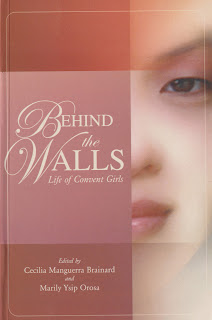

The following is an article by Gemma Cruz-Araneta. This is part of the book BEHIND THE WALLS: LIFE OF CONVENT GIRLS ( Anvil 2005), a collection of personal essays by graduates of Philippine Convent Schools. The collection includes writings by Neni Sta. Romana Cruz, Imelda Nicolas, Herminia Menez Coben, and others. For more information about the book, visit https://ceciliabrainard.com/book/behind-the-walls/ .

Gemma

Cruz Araneta graduated from Maryknoll

College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Foreign Service in 1963. She worked at the National Museum of the Philippines as Information

Writer and Chief Docent. In 1968, she was appointed Director. In 1965, Gemma won the Miss International

Beauty pageant at Long Beach, California — the first Filipina to bring home an

international beauty title

A

professional writer since she was nine, she has been a weekly columnist for

various national newspapers and magazines and has published six books: Makisig, Little Hero of Mactan, Hanoi Diary,

Fashion & Beauty for the Filipino Woman, Sentimiento: Fiction and

Nostalgia, Stones of Faith and El

Galeon de Manila, Un Mar de Historias (co-author).

Gemma studied in two convent

schools, St. Theresa’s College and Maryknoll College for a total of 15 years.

BENEVOLENT ASSIMILATION

Gemma Cruz-Araneta

copyright 2023 by Gemma Cruz-Araneta

AT MARYKNOLL COLLEGE, where I studied for eleven years, I was completely

enraptured by the ethereal magic of Catholic liturgy and religious pomp. Life

was a series of rituals that fortified the spirit. On first Fridays, a high

Mass was celebrated at the Marian Auditorium where we sang Gregorian chants and received the Holy

Eucharist. There were joyful processions to the Infant Jesus, floral offerings,

and sacred hymns to Our Lady. How mystical

it was to kneel in perpetual adoration

before the Blessed Sacrament,

resplendent in a golden monstrance. Sometimes, we were carried away by

religious fervor. A classmate once claimed that Our Lady appeared to her in the

chapel and when she was brutally murdered

the summer after, we were stricken with guilt for having doubted her.

However, I was

not sent to Maryknoll only for religious instruction. In my family, we were all

God-fearing, devout, thinking Catholics, proud of having two pious Jesuits, an

angelic Carmelite abbess and an eminent bishop in our midst. I was enrolled at

my mother’s alma mater, which was a convent school with irrefutable academic

standards. But I was transferred to Maryknoll College, ostensibly to learn

good, American English.

Since

language cannot be taught nor learned in a vacuum, my student life was

dichotomized by two perpetually contending perspectives. American English came with everything else

that was American -- images of an alien

lifestyle, cultural prejudices and preferences, and later in college,

policies and politics that often clashed with what I was learning at home. In

fact, the only common denominator of school and home was the Catholic religion.

Yet, I only have happy memories of Maryknoll. I had

favorite nuns while in the primary and secondary levels. Sister Catherine Therese was sweet, friendly

and energetic enough to teach us how to

do-si-do and sing “Oh, Susana.”

Sister Zoe Marie made us feel like Broadway stars. She produced and directed

Tekakwita, a play about the first

native American saint. She taught us how to decorate those Indian costumes; we

made bead necklaces and trimmed head bands with duck feathers. She lent us

books about native Americans and we felt we were authorities on the

subject. However, at home, there were

after-dinner comments about Tekakwita

and references to a “Philippine reservation” at the St. Louis Exposition. I suddenly remembered that Sister Zoe Marie

did say her father had been worried about her coming here and that he had told

her to buy a shot gun. It was only much later, when I had connected all the

dots that I finally understood what

they meant.

American English was taught systematically and

intensively. During those eleven years, I must have written hundreds of

compositions and book reports, fragmented and diagramed thousands of sentences,

honed tongue and vocal cords during interminable phonics classes. Our national language was also a compulsory

subject, but strangely enough, we could speak it only during that hour-long

class.

Had

the Department of Education sent a circular to all private schools forbidding

the use of the national language outside the classroom? To this day, my ex-classmates and I are outraged

at the way we were severely reprimanded

for speaking in the vernacular.

My nemesis was Sister Celine Marie who often caught me babbling in

Tagalog in the school cafeteria. She was not even our English teacher; she was

the Logic professor so I felt she had no right to threaten me with expulsion.

Besides, I was getting good grades in English. Because most of us were

bilingual at home, it was almost impossible not to use both languages (not

Taglish) in an animated conversation during our free time.

In college, the

dichotomy went beyond the language debate and into the realm of politics and

policies. In defiance to a Philippine law that dictated the inclusion of the

Rizal Course in the curriculum, only a

single lecture on the life of the national hero was given at Maryknoll. During

a Monday morning assembly at the Marian Auditorium, Sister Miriam Catherine,

the college dean, read a paper that compressed the required semesters. As a

footnote, we were enjoined not to read Rizal’s revolutionary novels, Noli Me

Tangere and El Filibusterismo, because the Archbishop of Manila had

declared them anti-Church. That really caused a furor at home where the works

of Philippine heroes, especially Jose Rizal’s,

were in the must-read list of even my bishop uncle.

And what else are

the nuns going to forbid? — my elders wanted to know. What about Philippine

history? That was how I found out that

Sister Joanna Marie had been assigned to teach Philippine History. An American

nun, teaching Philippine History? What

is this — Benevolent Assimilation? But,

anything for American English, I suppose.

To remedy that unacceptable situation, I was sent to the University of

the Philippines, for the entire summer, to take Philippine History and

Philippine Government I, which I had to

take all over again under Sister Joanna Marie.

After that, the dichotomy between school and home became

more glaring. Filipino political

leaders who were nationalist icons of my family — Claro M. Recto, Lorenzo

Tanada, Jose Diokno to name a few — were branded communists in school.

Non-alignment, self-reliance, neo-colonialism, US intervention, the military

bases, the CIA, the Parity Amendment, including

salvation outside the Catholic Church,

had irreconcilable definitions at

school and at home. But I survived all

that without becoming schizophrenic. Today I have a habit of looking at both

sides of the picture.

The Maryknoll nuns taught us good American English which

has become our comparative advantage in the extremely competitive labor market.

Under their tutelage, we became better Catholics, in thought word and deed.

But, although they instructed us to love God above all things, the nuns

could not show us how to be proud

of being Filipinos nor how to love the Philippines more than ourselves. Fortunately, many of us learnt that at home.

Read also:

Read also:

Neni Sta Romana Cruz's Growing up St. Scholastican

Herminia Menez Coben's Behind the Walls of St Scholastica College

Gemma Cruz-Araneta's Benevolent Assimmilation

Imelda M. Nicolas's Confessions of an Interna

Watch also: THE CEBUANA IN THE WORLD: Cecilia Manguerra Brainard Writing out of Cebu

Tags: #Philippineeducation #Filipinoschools #Catholicschools #missuniverse #missinternational #missphilippines #filipinabeautyqueens